|

DOI: 10.7256/2454-0641.2023.3.43956

EDN: VHZQVW

Received:

01-09-2023

Published:

08-09-2023

Abstract:

The article analyzes the challenges and prospects for cooperation between Europe and Latin America in the field of higher education. The aim of the paper is to identify the potential for interregional dialogue in the context of globalization. The methodology used is a comparative analysis of higher education systems in Europe and Latin America. As a result, it is shown that despite the Europeanization of Latin American education, there are still significant differences that need to be taken into account when transferring European experience. The priorities for further interaction – creation of a common educational space and scientific-innovative networks - are outlined. The results can be useful for developing a strategy of internationalization of education. The novelty lies in the systematic comparison of approaches to the modernization of higher education in the two regions. The conclusion is made about the need for effective coordination and search for optimal formats of dialogue between Europe and Latin America for the formation of a global educational space.

Keywords:

Higher Education, Europe, Latin America, Global Interuniversity Collaboration, Challenges, Prospects, International Cooperation, Academic Environment, Scientific and innovation networks, Research and development

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

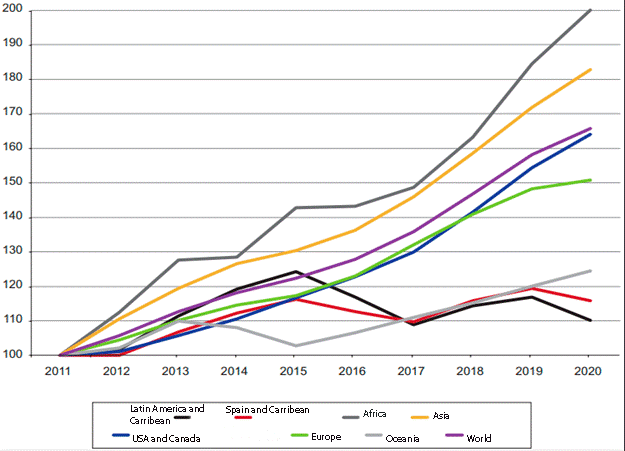

The role and functions of international cooperation in the field of higher education have undergone profound conceptual and instrumental changes over the past ten years, due to both the processes associated with increasing requirements for the quality and relevance of higher education institutions, and the generalization of the task of internationalization of teaching, research and educational institutions themselves. The attitude of higher education institutions to international cooperation has developed most significantly. This evolution is expressed in a change in the perception of cooperation: from considering it almost exclusively as a source of external financing and an additional element to considering it as an integral and strategic element for strengthening institutions and as an instrument for the internationalization of higher education systems. The purpose of this study is to analyze the challenges and prospects for the development of dialogue between Europe and Latin America in the field of higher education, taking into account the creation of a system of global interuniversity interaction. To achieve this goal, an extensive review of the literature on the research topic was conducted, which allowed identifying existing trends, problems and successful practices in the development of dialogue between Europe and Latin America in the field of higher education. Using the Case-Study method, an example of creating a system of interaction between two regions in the field of higher education was studied to identify factors contributing to strengthening cooperation. Comparative analysis was used to identify similar and different approaches to the organization of interuniversity cooperation. The scientific novelty of the research lies in the analysis of challenges and prospects for the development of dialogue between Europe and Latin America in the field of higher education with an emphasis on the formation of a global interuniversity system of interaction. The study combines current aspects of the development of higher education in Latin America, as well as analyzes practical solutions and approaches taken by the two regions to create partnerships. The results of the study provide recommendations for universities and international organizations seeking to develop cooperation between Europe and Latin America in the field of higher education. The analysis of the factors of successful interaction and overcoming obstacles can contribute to the expansion of international opportunities for students and researchers of both regions. The task of in-depth analysis of the dialogue between Europe and Latin America in the context of higher education is an important research issue. The processes of globalization and knowledge exchange have led to the need for closer cooperation between regions, especially in the field of education. In this context, the creation of a system of global interuniversity cooperation between Europe and Latin America seems to be an important direction with its own challenges and prospects. International cooperation has become a horizontal activity that influences the policy, organization and management of higher education and universities, the training of teaching staff, proposals for training students, postgraduates and continuing education, both full-time and virtual, the training and specialization of researchers, the process of scientific research, information and educational activities, and also for development cooperation through the role of universities as agents of cooperation. Functional multilateralism is being reassessed, especially through the proliferation of flexible cooperation tools such as networks and strategic alliances between participants. These tools enhance the benefits of cooperation by expanding the opportunities for interaction and forms of cooperation. The European-Latin American space is recognized as a favorable space for inter-university cooperation. However, it is necessary to take into account some conditioning factors, such as asymmetry in terms of the fragility of university systems, a different understanding of the role of cooperation and the degree of institutional commitment on the part of universities, as well as a noticeable heterogeneity in the quality and effectiveness of the currently implemented cooperation. Problems of higher education in Latin America: the need to develop a transatlantic dialogue Since the beginning of this century, Latin American countries have been experiencing a significant process of economic and trade growth, and consequently an increase in GDP, corporate profits, household incomes and government spending [1, pp. 39-40]. This situation has led to an increase in investments, both public and private, in higher education. On the other hand, the region continues to face unresolved problems, which the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) defines as "structural gaps", including, in addition to inequality and poverty, issues such as insufficient quality of education and health services, low progressiveness of fiscal policy and limited investment in research [2, pp. 45-53]. Thus, Latin America is in a position where two trends can develop: sustainable development with greater inclusiveness and social justice, on the one hand, or, on the contrary, a possible increase in the average income level, which is fraught with indefinitely postponing the solution of the above problems [3, p. 5]. All this is reflected in the nuances that characterize the position of higher education. Investments in research and development (R&D) in Latin America, despite significant growth in the last decade, still remain low compared to other regions of the world, as shown in Figure 1. For example, the share of funds coming from the business sector in Europe and Latin America in 2020 was 53% and 40% respectively. Figure 1. Percentage dynamics of R&D investments (in PPP dollars) in selected geographical blocks (2014-2020)

Source: El estado de la ciencia: principales indicadores de ciencia y tecnolog?a iberoamericanos / interamericanos 2022 // Organizaci?n de Estados Iberoamericanos URL: https://oei.int/oficinas/argentina/publicaciones/el-estado-de-la-ciencia-principales-indicadores-de-ciencia-y-iberoamericanos-interamericanos-2022 (accessed: 08/19/2023). Similarly, the analysis of the higher education enrollment ratio as a function of income, conducted by Hardy K. Based on the processing of data from household surveys conducted in eighteen Latin American countries, it indicates a significant difficulty of access to university education for the poor and vulnerable segments of the population, as well as to some extent for the middle strata (Table 1). According to the Organization of Ibero-American States, in order to achieve productive development with greater added value and greater equity of distribution, it is necessary to guarantee equal access to quality education by reducing disparities, overcoming dropout and exclusion problems, improving natural science education and encouraging scientific professions [4]. Table 1. Coverage of higher education in Latin America (age 18-23 years). | A country/Region | Social groups by income | Total by country or region | | The poor | Socially vulnerable groups | Middle class | Top class | | Venezuela | 45,1% | 52,7% | 65,2% | 85,7% | 53,4% | | Argentina | 36,8% |

41,5% | 53,6% | 93,1% | 49,3% | | Paraguay | 23,6% | 34,1% | 48,6% | 58,6% | 41,4% | | Colombia | 24,5% | 25,9% | 43,3% | 75,9% | 33,2% | | Brazil | 26,3% | 26,0% | 37,3% | 66,8% |

31,4% | | Latin America | 27,8% | 33,9% | 51,2% | 69,1% | 38,4% | Source: Hardy C. Estratificaci?n social en Am?rica Latina: retos de cohesi?n social. – LOM Ediciones, 2014. – P. 48. Moreover, in the period from 2012 to 2021, the number of articles published by Latin American authors in scientific journals registered in the Science Citation Index (SCI) doubled, with the exception of Brazil, which achieved an increase of 158% over the same period of time. However, this dynamic is explained, in particular, by the increase in the presence of regional journals in the collection of this database since 2007. The growth in the number of published articles is also observed in other international databases, but on a smaller scale [5]. As noted earlier, among the serious problems of Latin America are reducing inequality, strengthening social cohesion and spreading a sense of citizenship, which, of course, is connected with the system of education, health and social services. After all, universities face the task of educating citizens who are able to understand their social environment and critically comprehend the information they receive, on the one hand, and on the other – social security is a guarantee and a right in the face of risks that any person may be exposed to (poverty, illness, etc.). Science contributes to this: on the one hand, as the highest the rational basis of social organization and relationships with nature, on the other hand, as a tool for achieving the material goals of society. Achievements in the field of healthcare, food, telecommunications, transport, etc. contribute to improving the quality of life of the population in a significant part of the planet. From this point of view, the possession of concepts and products of scientific activity is a key element for achieving the cohesion of a society consisting of citizens. In this situation, Latin American universities should strengthen their ties with institutions and other entities present in the territories where they are located in order to be able to more adequately fulfill their obligations to train personnel for development. Prerequisites for the development of interregional dialogue: from the Europeanization of Latin American higher education to the creation of a partner network After the Second World War, Europe dominated the field of conceptual, theoretical and empirical developments on regional agreements and integration. Therefore, theories are often developed on the basis of European experience, and then often "exported" around the world, and Latin America is no exception [6, p. 61]. Higher education is one example of the export of regional experience from Europe to Latin America. During the conquest of America, university institutions established on the Latin American continent were built on the model of Salamanca or Alcala. The process of gaining independence was also not marked by a break with the models brought from Europe. The colonial university was replaced by the "Napoleonic model", in which special attention was paid to professions other than scientific research. During these years and up to the first years of the republic, education was strongly influenced by the ideas of Enlightenment, which in the case of the Andean countries were promoted by Simon Rodriguez, who believed that education was necessary for the formation of emerging states, and education in the spirit of freedom and equality was the only way to overcome ignorance [7, p. 27]. Garcia Moreno, for example, brought various religious orders and European pedagogical missions to Ecuador, including German Jesuits, into whose hands he handed over the management and operation of the National Polytechnic School. Eloy Alfaro also brought several pedagogical missions from Europe to the country, which allowed him to strengthen his political and educational project based on secularism, which allows dividing the ideological spheres of church and state [8, p. 42].

In the 1990s, due to the complexity of regional problems in Latin America, new forms of transnational cooperation began to appear in the field of health care and labor migration, as well as in certain areas considered key to improving market competitiveness, such as higher education and foreign investment [9, p. 36]. At the same time, the growth in the number of trade agreements between different countries has led to the need to fit into the global economy, where priority is given to knowledge and innovation. In this regard, the demand for educational services for training specialists in various fields increased, which was facilitated, in particular, by the logic of the Washington Consensus, which stimulated the creation of new universities and the expansion of their academic offer in many Latin American countries [10, p. 47]. Europe has also increased the supply of educational services, mainly postgraduate education, to Latin American countries, which has contributed to the development of cooperation between these two regions in non-economic areas. A number of educational institutions offer postgraduate education, both full-time and distance, providing payment opportunities and access to scholarships, which is beneficial to Latin American specialists. One of the countries that offered Latin America the largest volume of educational services was Spain, whose initiatives came mainly from one of the largest financial groups – Santander Group, which created the Universia Foundation, through which it promoted mobility, provided scholarships and financial support to both teachers and students [11, p. 128]. In this regard, there was interest in Europe in transferring the Bologna project to Latin America. This initiative was supported by a number of Latin American countries, including because in those years European globalization was perceived as not such a frightening force as "American, more understandable and humane than Asian, and more appropriate to the characteristics and customs of Latin Americans than Australian" [12, p. 52]. At the summit in Rio de Janeiro, the will for closer cooperation with Europe in the field of higher education was expressed. This marked the beginning of the creation in 1999 . The Common Area of Higher Education for the European Union, Latin America and the Caribbean (hereinafter ALCUE) [13, p. 415]. By 2002, when Proyecto Tuning had gained a foothold in Europe, the ALCUE member countries began to seek approval of the European proposal in various European bodies, which was called the Tuning-Latin America Project [11, p. 130]. The aim of this project was "to set up educational structures in Latin America, initiate a discussion aimed at identifying and exchanging information, improving cooperation between higher education institutions for the development of quality, efficiency and transparency" [14, p. 18]. It was assumed that it would be possible not only to standardize diplomas, stimulate student mobility, create joint projects, etc., but also to improve the quality of work of Latin American universities, which, due to the growing number of higher education institutions throughout Latin America, is questioned by a number of authors: Claudio Rama criticizes the commercialization and decline in the quality of higher education in Latin America Due to the rapid growth of private universities [15, p. 165], Simon Schwarzaman analyzes the risks of "massing" higher education in Latin America [16, p. 274]. The Tuning-Latin America Project initiative was presented and approved by the European Commission in 2003. In 2004, it entered into force and was implemented in Latin America without significant changes. It was argued that such policy coordination in the field of higher education arose because the desire for high competitiveness and compatibility of higher education is not only a European, but also a global problem [17, p. 18]. The implementation of the Bologna Program in Latin America has a number of features that should be paid attention to. Thus, the initiative did not come from Latin America, but from Europe, half of those who worked on it were Europeans, and the Latin Americans who participated in its implementation did not represent universities as a whole, so "it was simply assumed that what is good for Europe will be good for Latin America" [11, p. 140]. As Amitav Acharya notes in The International Spectator, "international recommendations were given that did not take into account standards deeply rooted in other types of regional, national, subnational social formations and groups," which created an implicit dichotomy between good global or universal standards and bad regional or local standards" [18, p. 5]. At the same time, neither the peculiarities of the various universities of Latin America, nor the peculiarities of their countries, their cultural diversity and national identity, which represent a dynamic different from the European one at the time of the creation of the European Higher Education Area, were taken into account. After all, "unlike old Europe, Latin America does not have a common political, economic, monetary or knowledge space to which one could appeal," so the implementation of this initiative may not bring the desired results [19, p. 42]. In addition, it assumed not only the creation of a competency-based education model, but also a change in financing models, efficiency requirements through the introduction of evaluation systems, as well as pressure towards closer relations with the manufacturing sector [19, p. 57]. For this reason, this project is criticized for its reductionist vision of education, which does not allow training specialists with a broad and critical vision, and, according to Gary Rhoads and Sheila Slaughter, creates "textbook" professionals who do not have the necessary training in the field of citizenship [20]. Thus, academic capitalism, which has a neoliberal ideological bias, was able to strengthen itself in Latin America, considering higher education not as a right, but as a simple market service. As an explanation, it can be noted that the models for assessing the quality of universities and educational programs originate in the assessment of industry quality standards and pursue goals similar to those of ISO standards.

The establishment of a higher education zone between Latin America and Europe, despite the successes achieved during its existence, has not yet been strengthened, and therefore it is not yet possible to conduct a broader analysis of its successes and/or failures. Nevertheless, some events were held, for example, the First Conference of Ministers of Higher Education of the European Union, Latin America and the Caribbean in Paris in 2000; the Second Conference of Ministers Responsible for Higher Education in Guadalajara (Mexico) in 2005; the First CELAC-EU Academic Summit in Santiago de Chile in 2013; the Second CELAC-EU Academic Summit in Brussels in 2015 and the Third CELAC-EU Academic Summit held in El Salvador in 2017. Among the goals that were outlined within the framework of these events is the creation of not only a common higher education space, but also a knowledge space leading to the integration of higher education with scientific research and innovation, for which it is necessary to appeal to the heads of state with a request to create regulatory and financial conditions for the consolidation of this space, as well as to promote the transformation of higher educational institutions. institutions to promote the integration of research and innovation systems. Within the framework of this research-based system, universities should move from the production of basic science for publication to the production of applied science in cooperation with industry for the development of patents, and with them a new source of income for the university [20, p. 391]. Thus, there is a danger that transnational corporations will become the main beneficiaries, since they will be able to absorb highly skilled and cheap labor, given the impossibility of attracting it by most Latin American countries due to the limited industrial and technological development characteristic of them. Conclusion The European-Latin American space is characterized by a large number of activities on inter-university cooperation, which are carried out within the framework of multilateral organizations and initiatives, bilateral intergovernmental agreements, inter-institute agreements, as well as spontaneously, as a result of personal relations between representatives of academic and scientific circles. One of the main challenges is the cultural and institutional diversity between these two regions. Differences in language, educational standards, and teaching methods can become an obstacle to effective interaction. However, it is this diversity that also presents potential prospects. The exchange of experience and best practices in the field of higher education between Europe and Latin America can enrich both sides and contribute to the development of innovations in the educational process. Another challenge is the uneven development of university systems in these regions. Europe has a long history of university education, while Latin America has faced various socio-economic challenges affecting the education sector. This may affect the level of training of students, the availability of education and its quality. However, the development of a system of interuniversity interaction can help reduce this unevenness through the exchange of experience and resources. The possibilities for expanding cooperation in the field of higher education between the two regions are still very extensive, given the existing set of universities and the interest shown in intensifying this interaction. Moreover, the creation of a clear European-Latin American structure can contribute not only to the use of new opportunities for cooperation, but also to the consolidation or reorientation of some current activities in order to improve the quality and effectiveness of such interaction. The creation of a system of global interuniversity cooperation can also have positive economic and social prospects. The exchange of knowledge and expertise between universities in Europe and Latin America can contribute to the development of scientific research, innovation and technological progress. This may have an impact on the development of economic sectors that depend on scientific and technological progress. For the effective implementation of the system of interuniversity interaction, it is also necessary to take into account political and socio-cultural aspects. Decision-making processes, resource allocation and the establishment of partnerships may depend on the political interests and socio-cultural characteristics of each region. It is necessary to find a balance between taking into account the sovereignty and interests of States and the need for cooperation in the field of education.

References

1. CEPAL (2015). Perspectivas económicas de América Latina 2015: educación, competencias e innovación para el desarrollo. Retrieved from https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/37445-perspectivas-economicas-america-latina-2015-educacion-competencias-innovacion

2. CEPAL (2021). Panorama Social de América Latina 2021. Retrieved fromhttps://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/47718/1/S2100655_es.pdf

3. Alonso, J. A., Glennie, J., & Sumner, A. (2014). Receptores y contribuyentes. Los países de renta media y el futuro de la cooperación para el desarrollo. Naciones Unidas/UNDESA, Nueva York.

4. Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos (2012). Ciencia, tecnología e innovación para el desarrollo y la cohesión social. Programa iberoamericano para la década de los bicentenarios. Retrieved from https://oei.int/oficinas/paraguay/noticias/ciencia-tecnologia-e-innovacion-para-el-desarrollo-y-la-cohesion-social-programa-iberoamericano-para-la-decada-de-los-bicentenarios

5. Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos (2022). El estado de la ciencia: principales indicadores de ciencia y tecnología iberoamericanos / interamericanos. Retrieved from https://oei.int/oficinas/argentina/publicaciones/el-estado-de-la-ciencia-principales-indicadores-de-ciencia-y-iberoamericanos-interamericanos-2022

6. Tayar, V. M. (2019). Евросоюз и Латинская Америка в контекстемежрегионального взаимодействия [The European Union and Latin America in the context of interregional interaction]. Современная Европа [Contemporary Europe], 4(89), 16-27.

7. Mora, J. G., & Fernández Lamarra, F. (2005). Debates sobre la convergencia de los sistemas de educación superior en Europa y América Latina. Educación Superior: convergencia entre América Latina y Europa. Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero.

8. Val, P. A., Cámara, C. P., & Eguizábal, A. J. (2009). Educación superior y sistemas de garantía de calidad. Génesis, desarrollo y propuestas del modelo de la convergencia europea. Omnia, 15(1), 37-56.

9. Riggirozzi, P. (2015). UNASUR: construcción de una diplomacia regional en materia de salud a través de políticas sociales. Estudios Internacionales (Santiago), 47(181), 29-50.

10. The World Bank (2008). Educación Superior en América Latina La dimensión internacional. Retrieved from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/ru/797661468048528725/pdf/343530SPANISH0101OFFICIAL0USE0ONLY1.pdf

11. Aboites, H. (2010). La educación superior latinoamericana y el proceso de Bolonia: de la comercialización al proyecto tuning de competencias. Cultura y representaciones sociales, 5(9), 122-144.

12. Bugarín Olvera, R. (2009). Educación superior en América Latina y el proceso de Bolonia: alcances y desafíos. Revista Mexicana de Orientación Educativa, 6(16), 50-58.

13. Azevedo, M. L. N. D. (2014). The Bologna Process and higher education in Mercosur: regionalization or Europeanization? International Journal of Lifelong Education, 33(3), 411-427.

14. De Garay Sánchez, A. (2008). Los acuerdos de Bolonia; desafíos y respuestas por parte de los sistemas de educación superior e instituciones en Latinoamérica. Universidades, 37, 17-36.

15. Rama, C. (2006). La tercera reforma de la educación superior en América Latina (p. 248). Buenos Aires: Fondo de cultura Económica.

16. Schwartzman, S. (2011). La educación superior en América Latina y el Caribe: vicios y virtudes del crecimiento acelerado. Revista da Avaliação da Educação Superior, 2, 267-282.

17. Salinas, N. H. B., & Néstor, H. (2007). Competencias proyecto tuning-europa, tuning.-america latina. Competencias Proyecto TUNING-Europa, TUNING-América Latina, 1-27.

18. Acharya, A. (2012). Comparative regionalism: A field whose time has come? The International Spectator, 47(1), 3-15.

19. Brunner, J. J. (2008). El proceso de Bolonia en el horizonte latinoamericano: límites y posibilidades The Bologna Process in the Latin American horizon: limits and possibilities. Tiempos de cambio universitario en, 119.

20. Rhoades, G., & Slaughter, S. (2010). Capitalismo académico en la nueva economía. Retos y decisiones, 389-410.

Peer Review

Peer reviewers' evaluations remain confidential and are not disclosed to the public. Only external reviews, authorized for publication by the article's author(s), are made public. Typically, these final reviews are conducted after the manuscript's revision. Adhering to our double-blind review policy, the reviewer's identity is kept confidential.

The list of publisher reviewers can be found here.

Although the Institute of Education is one of the most conservative social institutions, at the same time it is also one of the most modernized. And at the same time, since the appearance of the first universities in Western Europe, higher education has been acting as an important tool for the development of personality and, ultimately, of the whole society, in connection with which close attention has been directed at it in the developed countries of the world, and the problem of "brain drain" is increasingly coming to the fore in countries Asia, Africa, Latin America. In this regard, it seems important to address various aspects of the interaction of the regions of our planet, within which a system of global interaction of higher education institutions is being formed. These circumstances determine the relevance of the article submitted for review, the subject of which is cooperation between Europe and Latin America in the field of higher education: The author sets out to analyze existing trends, as well as identify problems and successful practices in the development of dialogue between Europe and Latin America in the framework of higher education. The work is based on the principles of analysis and synthesis, reliability, objectivity, the methodological basis of the research is a systematic approach, which is based on the consideration of the object as an integral complex of interrelated elements. The scientific novelty of the article lies in the very formulation of the topic: the author seeks to characterize the challenges and prospects for the development of dialogue between Europe and Latin America in the field of higher education with an emphasis on the formation of a global interuniversity system of interaction. Considering the bibliographic list of the article as a positive point, its scale and versatility should be noted: in total, the list of references includes 20 different sources and studies. The undoubted advantage of the reviewed article is the attraction of foreign literature, including in Spanish, which is determined by the very formulation of the topic. From the sources attracted by the author, we will primarily point to the materials of the electronic resources of the Organization of Ibero-American States on Education, Science and Culture. Among the studies used, we note the works of Gary Rhoads and Sheila Slaughter, S. Schwartzman, K. Rahm and other authors, whose focus is on various issues of cooperation between Europe and Latin America. Note that the bibliography of the article is important both from a scientific and educational point of view: after reading the text of the article, readers can turn to other materials on its topic. In general, in our opinion, the integrated use of various sources and research contributed to the solution of the tasks facing the author. The style of writing the article can be attributed to scientific, at the same time understandable not only to specialists, but also to a wide readership, to everyone who is interested in both international cooperation in the field of education in general and contacts within the higher education system in particular. The appeal to the opponents is presented at the level of the collected information received by the author during the work on the topic of the article. The structure of the work is characterized by a certain logic and consistency, it can be distinguished by an introduction, the main part, and conclusion. At the beginning, the author defines the relevance of the topic, shows that "international cooperation has become a horizontal activity that affects the policy, organization and management of higher education and universities, on the training of teaching staff," etc. The work shows that if "in Europe there is a long history of university education, while Latin America I have faced various socio-economic problems affecting the education sector." However, as the author rightly points out, it is "the development of a system of interuniversity interaction that can help reduce this unevenness through the exchange of experience and resources." The work also highlights such examples of cooperation as the First Conference of Ministers of Higher Education of the European Union, Latin America and the Caribbean in Paris in 2000; the Second Conference of Ministers Responsible for Higher Education in Guadalajara (Mexico) in 2005; the CELAC-EU academic summits in 2013, 2015, 2017. The main conclusion of the article is that "the European-Latin American space is characterized by a large number of activities on interuniversity cooperation, which are carried out within the framework of multilateral organizations and initiatives, bilateral intergovernmental agreements, interinstitutional agreements, as well as spontaneously, as a result of personal relations between representatives of academic and scientific circles." The article submitted for review is devoted to an urgent topic, will arouse readers' interest, is provided with a drawing and a table, and its materials can be used both in training courses and in the framework of the development of cooperation between universities in Europe and Latin America. In general, in our opinion, the article can be recommended for publication in the journal "International Relations".

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Eng

Eng