|

DOI: 10.7256/2454-0595.2023.3.41034

EDN: FGAEFF

Received:

14-06-2023

Published:

21-06-2023

Abstract:

The object of the study is the relations of nature management in the Melanesian States, the subject is the legislation and doctrine in the field of exploitation of natural resources of the countries of Melanesia: the Commonwealth of Australia, the French Republic, the Republic of Vanuatu, the Republic of Fiji, the Solomon Islands, the Republic of Nauru, the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, the Republic of Indonesia. The author examines the features of the state natural resource apparatus in various jurisdictions, first of all, the management of the environment and subsoil use by executive authorities. The article examines the institution of ownership of land and subsoil, the permissive procedure for the use of natural objects, as well as contractual and directive grounds. In addition, the author addresses the problems of implementing the norms of international maritime law, explores the legal regime of the Australian Antarctic territories. The work is a new round in the theory of natural resource law of foreign countries, the relevance of the research is due to the theoretical and practical significance of the content of the article, which reflects domestic economic interests in Oceania. The scientific novelty of the presented work lies in the originality of the conclusions and the work itself, which contains fundamentally new information on the subject of research. Legal studies of Melanesia are insignificant, one of the few Russian scientific publications about this Pacific region is presented to your attention, while the available works are largely outdated, and some jurisdictions are covered in the domestic press for the first time. The author discusses with foreign scientists, analyzing foreign doctrine and legislation, and suggests using the experience of the Solomon Islands in the Russian Federation. At the same time, violations of the implementation and implementation of the norms of international maritime law in the Pacific Ocean by the Melanesian States are noted, as well as cases of the establishment of a national legal regime of Antarctic territories; it highlights not only the seizure of resource bases by the collective West, but also the incorporation of sovereign States, which is a modern form of establishing colonial dependence.

Keywords:

land ownership, subsoil ownership, natural resource law, continental shelf, International Maritime Law, Melanesia, mineral lease, mining administration, mining licence, melanesian foreign investment

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

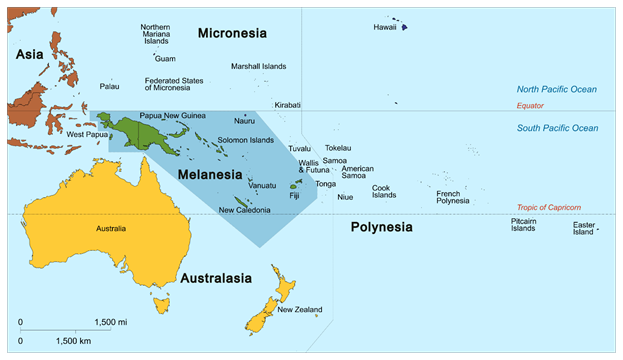

Melanesia is a part of Oceania – an area of the Pacific Ocean,[1] adjacent to the Northeast of the continent of Australia,[2] including groups of islands on which 8 states are located (the Commonwealth of Australia, the French Republic, the Republic of Vanuatu, the Republic of Fiji, the Solomon Islands, the Republic of Nauru, the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, the Republic of Indonesia),[3] dependent state entities [4] and the external territories of some of them. [5] The article continues the narrative about the features of the Pacific natural resource law, the beginning of which was published in the previous issue of the journal. [6]

The legal regulation of environmental management in countries whose isolated territories are located in the study area requires a separate study, with the exception of regional specifics.[7] The purpose of our study is to identify the features of the legal regulation of subsoil use in Melanesian jurisdictions. To achieve this goal, it is necessary to solve the main tasks: to study the normative legal acts regulating the relations of subsoil use in Melanesia, as well as the relevant doctrine, offering the reader their analysis. There were no significant works on the study of natural resource law of foreign countries, in particular, Oceania states. The recognized and only classical scholar in this field is Professor B.D. Klyukin[8], the rest of the works are fragmentary and, at most, qualitatively focused on one jurisdiction (Johannes Rat and others), or briefly characterize the general provisions or conceptual apparatus of legislation on subsoil and subsoil use of a number of key jurisdictions (D.V. Vasilevskaya[9], Mirkerimova N.F.K.[10], Agafonov V.B.[11] and others). Meanwhile, the comparative legal method is not used in some scientific and qualification works (Shamordin R.O. and others)[12], submitted for protection to the Institute of Legislation and Comparative Law under the Government of the Russian Federation, which makes more significant the published studies of natural resource law of foreign countries necessary for the use of foreign experience, as well as economic cooperation. Job offers and the information contained in it can be used both by the Russian legislator and by domestic organizations of the raw materials sector of the economy. The author in the article operated with universal dialectical, logical, historical, formal-legal, comparative-legal and other research methods. According to the reviewers, the scientific novelty of the publication consists in introducing new legal information, previously unrevealed facts, conclusions on the text of the work into circulation for an interesting readership. Following the recommendation of the publishing house, we have chosen the regional principle of presenting the scientific material presented to the reader of the study. Australian Commonwealth The legal regime of subsurface use in Australia is discussed in detail in one of the recent publications of the publishing house.[13] At the same time, it does not affect the Australian territories in Melanesia and other areas of the Pacific, Indian, and Southern Oceans adjacent to the Melanesian part of Oceania, and included by the scientific community in the study region – Australia and Oceania (External territories of Australia): Norfolk Island; Christmas Island Island); Cocos Islands (Cocos (Keeling) Islands); Ashmore and Cartier Islands; Coral Sea Islands Territory; Heard Island and McDonald Islands; Australian Antarctic Territory.[14] The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts of the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts, Australian Government) manages Australian territories not included in the Union regions. At the same time, the Australian Antarctic Territory, Heard and McDonald Islands are handled by the Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment of the Australian Government (Department of the Agriculture, Water and the Environment).[15] Within the Australian state borders, there are Union-wide regulatory legal acts on nature management, [16] as well as special environmental and natural resource legislation of the Commonwealth adopted for isolated territories.[17] Ashmore and Cartier Islands[18] In the middle of the XIX century, industrial reserves of phosphates were discovered on these islands, and later Indonesian hydrocarbon deposits – Jabiru and Challis (Jabiru and Challis oil fields) bordering the 12-mile territorial sea were discovered. Australia and Indonesia Maritime Boundary Agreement 1996 provides for the delimitation of the maritime borders of the two states in order to delimit the extraction of carbon from the subsurface, fishing, transportation of extracted raw materials and other shipping. The Ashmore and Cartier Islands are currently equipped with military infrastructure to provide temporary basing, refueling of ships and aircraft of the Royal Australian Navy (The Royal Australian Navy),[19] patrolling the waters of the islands to protect them from illegal exploitation of natural resources of the ocean, seabed and subsurface underwater areas. The Customs and Border Protection Service of Australia (Australian Customs and Border Protection Service) controls the turnover of natural resources of the isolated territory and the adjacent marine zone.[20] This indicates the intensive use of minerals and biodiversity of the region, the reserve of which is provided by the creation of the Ashmore Reef National Nature Reserve (Ashmore Reef National Nature Reserve) with an area of 583 square kilometers. [21] The National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act of 1975[22], which was in force from March 13, 1975 to July 16, 2000, established and ensured the functioning of this conservation area. It was replaced by the Environmental Reform (Consequential Provisions) Act 1999). Living resources, first of all, are preserved for the supply of the Australian military stationed in the region, supporting not only the legality and safety of nature management, but also controlling the south Asian waters from a military-political point of view.

The Ashmore and Cartier Islands were transferred by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the Northern Territory of the Commonwealth in 1933, and directly to Australia in 1978. Thus, the administration of environmental management is conducted by the Australian government directly by the above-mentioned ministries, the management of hydrocarbon production is delegated to the Ministry of Mining and Energy of the Northern Territory of the Commonwealth of Australia (Northern Territory Department of Mines and Energy). Historically, the laws of the Commonwealth, the Northern Territory (1933-1978 – the period when Ashmore and Cartier entered the Northern Territory of Australia, as well as regulatory legal acts in the field of hydrocarbon production) and the resolutions of the Governor–General of Australia have been in force on the islands. Coral Sea Islands The Coral Sea Islands Act 1969[23] created a separate territory with an area of about 780,000 square kilometers of coral and sandy islands beyond the Great Barrier Reef.[24] Since 1901, the Australian Navy has controlled the area in question, however, the sovereignty of the English monarch over the Coral Sea islands has been exercised by the Australian Commonwealth since 1968, which bought them from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which caused this acquisition not to be included in the territories of the Union members, as well as the management of the islands directly by the Australian government.[25] Nature reserves have been established on the Coral Sea islands: Coringa-Herald, Lihou Reef Middleton, Elizabeth Reefs on the basis of the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975. The territory and the reserves created on it are administered by the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, Australian Government[26] [27] and the Ministry of Fisheries, Agriculture and Forestry of Australia (Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Australian Government). [28] Commercial fishing is licensed by the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (Australian Government).[29] The Royal Navy and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service monitor the territory of the islands from the sea and air. On the Coral Sea Islands, in addition to the regulatory legal acts of the Commonwealth of Australia, the laws of the Australian Capital Territory, as well as the resolutions of the Governor-General of Australia, apply. The Supreme Court of Norfolk Island (with incorporated federal judges) exercises criminal jurisdiction over environmental crimes committed on the Coral Sea Islands. Thus, the territory and waters of the Coral Sea Islands are the reserve of the English Crown, necessary for mineral, food and other raw materials for Australia during a period of scarcity of natural resources, including periods of global conflict, including the current supply of the Australian Navy, patrolling the waters not only of Melanesia, but also of the Asia-Pacific region as a whole. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Commonwealth of Australia, having a common monarch, use the resource base of the Coral Sea Islands to ensure a military presence in Oceania, dominance in this region together with the United States of America. Territories of Christmas Island and the Cocos Islands and the Indian Ocean The Administrator of the Territories in the Indian Ocean (Administrator of the Territories of Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands)[30] – the Christmas Islands, as well as the Cocos Islands (Keeling), is appointed by the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia and represents the Australian Government in relations with isolated territories and foreign persons. The administrator is responsible for the organization of disaster prevention and elimination of their consequences, the management of territories in emergency situations. At the same time, 51 public services are provided to organizations and residents of the territories under consideration by the Government of Western Australia. Scientific research of diverse flora and fauna, biosecurity, aquaculture, waste, farmland and natural resources of Australian territories in the Indian Ocean is carried out on applications accepted by the Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and Arts of the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia. This Commonwealth executive organ organises the operation of Christmas Island and the Cocos Islands. Christmas National Park occupies two-thirds of Christmas Island and is managed by Parks Australia.[31] The Local Government Act 1995[32] provides for the creation of a local government body – the Christmas County Council, which coordinates land use, water use and forest management, construction and subsoil use under Australian law. Meanwhile, the territory was transferred to the administration of Australia only in 1958 by Singapore, which was a British colony. Until 1992, the laws of Christmas Island were largely based on Singaporean colonial legislation, although the Christmas Island Act 1958[33] created the necessary basis for the application of Australian law and governance. This territory in the Indian Ocean has no independent legislation, the regulatory legal acts of the Commonwealth of Australia and Western Australia form the legal basis of the studied administrative territorial unit. The Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts of the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia, in full cooperation with the administrator of the Christmas Islands, fully manages them, but does not carry out law enforcement and defense functions, this is occupied by police, border guards, customs officers and the military of Australia. At the same time, the acts of the authorized Union Minister have greater legal force than the laws of Western Australia, which is a local feature. Christmas Island has been used since 1891 for phosphate mining, which led to the introduction of an environmental fee for the restoration (reclamation) of spent phosphate mines. As a result of the strategic assessment, a plan for the sustainable development of the territory was developed, which defines actions for the creation of a land use map and the implementation of environmental protection.

The Cocos Islands (Keeling Islands) are an external territory of Australia on the basis of article 122 of the Constitution of Australia. They, like Christmas Island, do not have a territorial government, and are headed by the same administrator, run by the same ministry, have a local Coconut Islands County Council on the same basis, and apply the laws of Western Australia in addition to Commonwealth regulations. Consequently, the law, system and governance structure of both Australian Territories in the Indian Ocean are similar. In 1955, the Cocos Islands passed from the control of the British colonies of Ceylon, Straits Settlements and Singapore under the jurisdiction of Australia (The Cocos (Keeling) Islands Act 1955)[34], on April 6, 1984, by universal vote of the islanders (Act of Self Determination 1984), it was decided to integrate into the Australian Commonwealth. Territories Law Reform Act 1992 marked the complete transition of the Cocos Islands to Australian law. [35] The Cocos (Keeling) Islands form the Pulu Keeling National Park,[36] their economy is developing due to tourism and fishing, there is no subsurface use and there is no plan for the development of this Australian territory due to its significant actual integration with the People's Republic of China, which has been implementing since 1986 demographic and economic expansion to the Cocos Islands of Australia. Norfolk Island The Administrator of Norfolk Island is appointed by the Governor-General of Australia and represents the Commonwealth Government on the island.[37] However, Norfolk, colonized by the British at the same time as the Australian continent, became part of Australia only in 1901, was governed until 1979 as an external territory, autonomous since 1979. In 1979 – 2016, the Norfolk administration performed local, regional and federal functions, the territory was self-governing until July 1, 2016. By the Norfolk Island Legislation Amendment Act 2015 and Related Acts (Norfolk Island Legislation Amendment Act 2015), the Territories Legislation Amendment Act 2016 and other laws, Norfolk Island was transferred to Australian jurisdiction, self-government ended. The Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Environment of the Australian Government became the administrator of the Commonwealth laws in relation to Norfolk, received this external territory into its administration. On the basis of the Law on Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999), Norfolk Island National Park and Norfolk Marine Park were formed. Philip Island is declared a national park under the management of Parks Australia. The following reserves are included in the Commonwealth Heritage List: Nepean Island Reserve and Selwyn Reserve. Environmental protection is carried out jointly with the Norfolk Island Regional Council. The Queensland Government, based on an agreement with the Australian government, has been providing public services in Norfolk since January 1, 2022 (Intergovernmental Agreement on State Service Delivery to Norfolk Island). [38] The Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts of the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia also administers Australian laws on the external territory of Australia – Norfolk Island, communication between federal ministries and the local council for the management of Norfolk is carried out by its administrator. Norfolk Island is a recreational facility, used as a reserve point for the placement of the English monarch and the British leadership if necessary to move it from the territory of the United Kingdom, which is why it was for a long time the most isolated Australian entity with the focus of control levers at all levels from one person – the administrator of Norfolk, which significantly excluded the leakage of information about the purposes of the intended use of the external territory. and the true reasons for the actual and legal separation of Norfolk. The demographic picture of Norfolk and the religious composition indicate the predominance of the English and Scots on the island – the service staff of the sovereign of the Australian Commonwealth – the King of England. Heard and McDonald Islands The Heard Island and McDonald Islands Act of 1953 (Heard Island and McDonald Islands Act 1953) ratifies the admission to the Commonwealth of Australia of the relevant territories of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a sub-Antarctic administrative-territorial unit administered directly by the Government of Australia by two ministries: the Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts, and also the Ministries of Agriculture, Water and Environment.[39] They implement the Law on Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999), territorial island acts – Regulations on Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation of 2000[40], Regulation on Management and Environmental Protection [41], - in relation to the Heard and McDonald Marine Reserve. The geological study of the seabed, preparation for uranium mining and other nuclear activities are carried out here. The Law on the Protection of the Sea (Prevention of Pollution from Ships) Act 1983)[42] is implemented by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority[43], and at the same time the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships of 1973 and the subsequent Protocol of 1978 to the relevant Convention (MARPOL 73/78) (Act implements the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships of 1973 and the subsequent 1978 Protocol to the Convention – MARPOL 73/78). Consequently, anthropogenic activities for the exploitation of the marine environment are carried out in the waters of Heard and McDonald Islands.

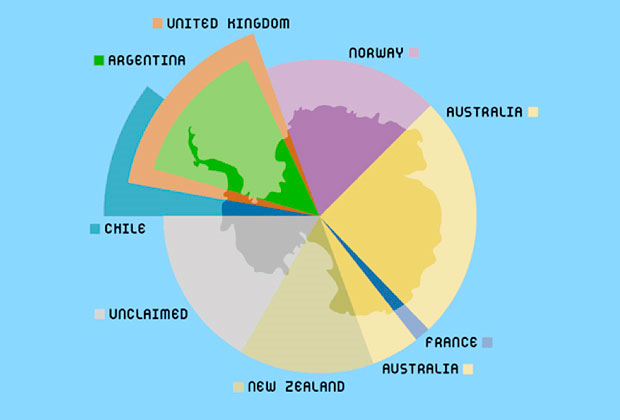

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) has protected the marine animals of the region since July 1, 1975, as has the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling (The International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling), signed by Australia in 1946. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS 1982) entered into force for Australia in 1982, invoking it to prohibit fishing, scientific and hydrographic research within the territorial sea of the external territory of the Commonwealth of Australia in question. This indicates the special status of the territory as a military-industrial facility and a springboard for the development of Antarctica. On the Heard and McDonald Islands, there are also: the Convention on the Protection of the World Cultural Heritage; the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Convention); the Convention on the Protection of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (Bon Convention); the Agreement between the Governments of Australia and the People's Republic of China on the Protection of Migratory Birds of their Environment; the Agreement between the Governments of Australia and Japan on the Protection of Migratory Birds and Endangered Birds and their Environment; the Agreement between the Governments of Australia and the French Republic on Cooperation in the Marine Areas Adjacent to the Southern and Antarctic Territories of France, Heard Island and McDonald Islands; the Convention on Biological Diversity; the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels; Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. It is noteworthy that small islands have become the subject of international legal regimes in the field of environmental management established by the great Powers.[44] Meanwhile, the islands of Heard and McDonald are not covered by the Antarctic Treaty, which distinguishes it from another part of the Australian Commonwealth, recognized only by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, New Zealand, the French Republic and the Kingdom of Norway – the Australian Antarctic Territory. Australian Antarctic Territory[45] The recognition by individual countries of the State sovereignty of the Commonwealth of Australia over a part of Antarctica in violation of international law is based on the claims of these subjects of international law to other sectors of Antarctica. The Australian Antarctic territory is, as it were, open to scientists from other countries by virtue of the international legal obligations of the Australian Commonwealth, which does not prevent other States from exercising treaty rights, but proclaims the spread of Australian jurisdiction in Antarctica over an area comparable to half the surface of the People's Republic of China, but the population of this region of the globe is about 15 million times smaller than the Chinese - about a thousand a man.

The interest of economically strong States is aroused not only by Antarctica, but also by the colossal Antarctic continental shelf, for which the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Commonwealth of Australia, the French Republic, the Republic of Argentina, the Republic of Chile, the Kingdom of Norway and New Zealand have prepared applications to the International Seabed Authority.[46] Mining in Antarctica is prohibited indefinitely by the Protocol on Environmental Protection (Madrid Protocol). Meanwhile, environmental protection and nature management is conducted in the Australian Antarctic Territory under the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia by two ministries: the Ministry of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts, as well as the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Environment. The Australian Antarctic program is led by The Antarctic Department (The Australian Antarctic Division of The Australian Government's Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water), in addition, the Australian Antarctic Strategy and the corresponding plan (Australian Antarctic Strategy and 20 Year Action Plan Update) have been adopted.[47] French Republic France is a unitary state, consisting of 26 subjects – administrative territorial units of the first level, including three overseas special administrative-territorial entities: New Caledonia; Clipperton; French Southern and Antarctic Territories, which have charters that take into account the own interests of each of them as part of the Republic (Article 74 of the French Constitution).[48] Charters may provide for the autonomy of the relevant subjects of the state and limit the application of French organic laws on them, change the subject matter of regional legislative authorities, detracting from the Republican parliament. [49] New Caledonia New Caledonia (Nouvelle-Cal?donie) is an overseas special administrative–territorial entity of the French Republic[50], which is governed by the High Commissioner of New Caledonia, appointed by the President of the French Republic.[51] Two Deputy High Commissioners are in charge of environmental management and energy, and lead the part of the commissariat dealing with natural resource relations. Article 76 of the French Constitution provided for the right of the population of New Caledonia to self-determination by holding a three-time referendum on secession from the Republic that concluded the Noum?a Agreement with the Territory (Accord de Noum?a).[52] The final tritium referendum was held in 2022, at which about 95% of Caledonians, with a turnout of 44%, voted for integration into the French Republic and against leaving it. Accord sur la Nouvelle-Cal?donie[53], signed on May 5, 1998, provides for the adoption of the French organic law on New Caledonia.[54] Loi n° 99-209 organique du 19 mars 1999 relative ? la Nouvelle-Cal?donie replaces the charter of New Caledonia and is adopted by virtue of the Treaty of Noum?an. The provinces and municipalities of the French Overseas special administrative territorial entity under study are territorial units of the French Republic (the third section of the law), and after the referendum this region has the status of a department.

Sections 6 and 18 of the Organic law under consideration establish the right of ownership of land in the following forms: private, State and ordinary (traditional). Public and private land are negotiable. Traditional lands are inalienable, non-transferable, unchangeable and not subject to seizure, their regime is regulated by customs. Such lands may be owned by citizens and organizations, they consist of reserves; as well as lands allocated to local special law groups (Kanaks – indigenous people of New Caledonia)[55]; and lands following the real estate erected on them, even when transferring this property to persons of ordinary law (French citizens born outside New Caledonia; foreigners; Kanaks and other citizens of the republic born in New Caledonia, but who have assumed ordinary civil status). Consequently, indigenous people, ordinary citizens and organizations can own traditional lands if this traditional land serves their buildings. In addition, legal capacity in New Caledonia depends on the civil status: general or special, the content of which is disclosed in sections 7-19 of the Organic Law. On the basis of the twentieth section of the Law, the provinces exercise, on a residual basis, those powers that are not delegated by the French Republic of New Caledonia, which has a regional parliament. France is responsible for environmental protection, while New Caledonia regulates and exercises the rights to explore, exploit, manage and conserve the natural, biological and non-biological resources of the exclusive economic zone, as well as rules concerning hydrocarbons, nickel, chromium, cobalt and rare earth elements. The economic analysis of the region indicates the concentration of a quarter of the world's proven reserves of these minerals in New Caledonia, however, the reliability of this information is subject to additional verification. At the same time, it was the colossal reserves of iron and other listed minerals as the economic basis of independence that gave rise to New Caledonian separatism, which was stopped by the metropolis in a democratic way. New Caledonia as a region of France, after taking into account the opinion of the advisory committee on the mining industry and the Mining Council, adopts, on the basis of section 39 of the organic law, a plan for the development of minerals describing the mining property used (mining enterprises); prospects for the exploitation of deposits; guidelines for environmental protection during the exploitation of deposits; a list of territories subordinate to the special mining police; directions of development of rational subsoil use; principles of mineral export policy. The New Caledonia Mining Advisory Committee consists of representatives of the French Republic, representatives of the Government of New Caledonia, representatives of the bicameral regional Parliament – the Congress of New Caledonia and the Senate of Customary Law of New Caledonia, representatives of provinces and municipalities of New Caledonia, industry delegates of trade unions, as well as environmental associations. He is consulted by the New Caledonian Congress on draft laws, and the New Caledonian municipal authorities on draft acts of the provincial assembly, if they relate to hydrocarbons, nickel, chromium, cobalt or rare earth elements and do not relate to the procedure for approving foreign direct investment. The Mountain Council consists of the President of the Government of New Caledonia, the Presidents of the provincial assemblies or their representatives, and the High Commissioner of New Caledonia, who heads the Mountain Council. The Congress of New Caledonia consults with the Mining Council on bills related to hydrocarbons, nickel, chromium, cobalt and rare earths related to foreign direct investment. Provincial assemblies are also consulted with him on draft regulatory legal acts of local significance affecting subsurface use within the boundaries of the respective municipalities. A feature of the New Caledonian property system is the presence of public and private ownership of land in France, New Caledonia, provinces and communes. Thus, the State, its subject and municipalities in New Caledonia have not only republican and regional state property, and municipalities have municipal property, there is no municipal property in New Caledonia at all, provinces and communes use the state property of the unitary republic transferred to them for use. Public legal entities – The French Republic, New Caledonia and its municipalities have the right of private ownership and the right of public ownership, which is unique. This means that land and other natural resources can be in the state ownership of public entities, as well as in their private or public ownership. Ownerless lands become the property of New Caledonia, and not municipalities as in British-controlled states. But it is the provinces of New Caledonia that regulate and exercise the rights to explore, exploit, manage and preserve the biological and non-biological natural resources of inland waters, harbors and lagoons, their soils and subsoil, as well as the bottom and subsoil of the territorial sea (section 46 of the Organic Law). The Economic, Social and Environmental Council of New Caledonia advises the regional Parliament and representative bodies of local self-government on environmental protection, its functions are also provided for in the organic law of the Noumean Treaty. There are five environmental executive authorities in New Caledonia: · Territorial representation of the French Bureau of Biodiversity (l'Office fran?ais de la biodiversit?), established on January 1, 2020 under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Transformation, Territorial Unity, Food Sovereignty and Agriculture (Transition ?cologique et de la Coh?sion des territoires et de l'Agriculture et de la Souverainet? alimentaire), which manages and protects marine environment of New Caledonia, as well as flora and fauna, implementing environmental policy and environmental advocacy;

· territorial representation of the Environmental Transition Agency (l'Agence de la transition ?cologique), which is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environmental Transformation, Territorial Unity, Food Sovereignty and Agriculture, as well as the Ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation (minist?re de l'Enseignement sup?rieur, de la Recherche et de l'Innovation), engaged in the transfer of the economy to energy-saving technologies, renewable energy sources, tax incentives for clean production, expertise of environmental projects, modernization of waste management; · The Agency for Rural Development and Land Management of New Caledonia (Agence de D?veloppement Rural et d'Am?nagement Foncier) is an operator of land reform of the overseas special administrative-territorial entity of the French Republic of New Caledonia, engaged in land allotments of the usual regime, restitution of Kanak lands (conversion of ordinary lands into traditional ones), land security and land valuation, assistance in land use planning, support for the development of agriculture; · The Office of the State Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Environment for New Caledonia (La direction du service d'?tat de l'agriculture, de la for?t et de l'environnement) functions under the leadership of the High Commissioner for New Caledonia in the implementation of international obligations in the field of ecology and nature management, local initiatives and projects, financial management of agricultural and natural resource sectors of the economy; performs under the patronage of the French Minister of Agriculture and Food (Sous l'autorit? du ministre de l'agriculture et de l'alimentation) the administration of agriculture in New Caledonia; performs under the auspices of New Caledonia the organization of agricultural training and management of natural resources; · The Department of Industry, Mining and Energy of New Caledonia (Direction de l'Industrie, des Mines et de l'?nergie de la Nouvelle-Cal?donie) was established in 1873 as Bureau des Mines - the Mining Administration of New Caledonia, which acted as the operator of mining legislation and inherited this function, to which mining supervision and environmental monitoring were added environment, as well as the development of energy and natural resources of this special overseas territory. The Department of Industry, Mining and Energy of New Caledonia (Direction de l'Industrie, des Mines et de l'?nergie de la Nouvelle-Cal?donie) consists of six departments and a laboratory for the study of minerals, it performs the following functions: · tariff regulation of prices for hydrocarbons and electricity, technical control of power transmission lines, financing of energy-saving measures; · coordination of mineral resources development (mining cadastre management, mining police, export control, statistics); · control of production activities that may have an impact on the environment, health and safety of people (police of classified installations, control of equipment operating under pressure, legislative metrology); · Providing the best knowledge of the terrestrial and marine geological structures of New Caledonia to justify land-use planning policies for sustainable development. The Department carries out mining supervision, including in relation to oil and gas companies operating the New Caledonian deposits: Mobil, SSP, TOTAL Pacific, SLN DBO, Enercal N?poui, Vale, as well as industrial supervision of waste disposal and turnover of explosives used for the extraction of solid minerals.

The Department of Industry, Mining and Energy of New Caledonia is responsible for the proper execution of the Code minier de la Nouvelle- Cal?donie. Laurent L'Huillier, Tanguy Jaffr?, Adrien Wulff in the book "Mines et Environnement en Nouvelle-Cal?donie: les milieux sur substrats ultramafiques et leur restauration" on 30-31 pages describe environmental requirements for subsurface use, listing regulatory legal acts regulating this area: Code minier 2010 (Loi du pays n° 2009-6 du 16 avril 2009 relative au code minier de la Nouvelle-Cal?donie (partie l?gislative)), D?lib?ration n° 104 et Fonds Nickel, Code de l'environnement de la province Nord, Code de l'environnement de la province Sud.[56] I would like to disagree with these authors, limited to the listed regulations establishing the legal regime subsoil use in New Caledonia. These New Caledonian environmental and natural resource acts were adopted by the Parliament of New Caledonia under the jurisdiction of a special overseas administrative-territorial unit of the French Republic, however, the list of these acts is incomplete. The authors do not take into account environmental legislation and legislation on subsoil and subsoil use of the French Republic, as well as acts of the French administration, documents of provinces and communes. Meanwhile, especially after the final referendum on the self-determination of New Caledonia, the legal regime of subsoil use and environmental protection is established by French republican legislation and regulated by New Caledonian and municipal regulatory legal acts on a residual basis. The exploitation of solid minerals on land is still based on the permits of local assemblies, agreed with the French Republic through advisory institutions: the mining committee and the Mining Council. At the same time, the service of mining inspectors, as, for example, in the Australian Union, is called the mining police, whose activities are regulated by New Caledonian law by virtue of the organic law. Obtaining a permit for the use of mineral resources is preceded by an environmental impact assessment by the mining company and public hearings. There are two types of subsurface use: geological exploration of the subsurface and exploitation of the subsurface (industrial exploration and development), in addition, there is communal exploitation of the subsurface – a type of use of deposits to meet the public needs of the region. A subsurface use application for obtaining the right to search and extract solid minerals must contain a plan for the reclamation of the deposit. The assemblies give the subsoil user permission to use subsurface areas (zones mini?re du projet) for a period determined by them, which the local authorities can extend at the request of the owner of the relevant permit. Concessions for the use of the subsoil of the land and sea are concluded by the High Commissioner of New Caledonia under the legislation of the French Republic, which regulates all types of nature management in the Pacific Ocean. The range of subjects for obtaining the right to use the subsoil is not limited, but the admission of foreign investors to the deposits is carried out by the republican authorities. France, New Caledonia, provinces and communes may establish State and municipal institutions for the implementation of subsoil use. Uranium mining is carried out only by state-owned companies on the basis of a special permit issued by the French Government. Thus, New Caledonia is a source of a significant amount of minerals entering industrial circulation, has a centuries-old history of subsurface exploitation and the development of the environmental protection system as part of the French Republic, which actively uses the mineral resource base of its overseas special administrative-territorial entity in connection with the trends of decentralization of the region and in order to avoid the expansion of economic activity in the region. from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the United States of America, the People's Republic of China. Republic of Vanuatu Vanuatu (R?publique du Vanuatu / Republic of Vanuatu) was a Franco–British condominium colony until 1980, formally an independent state since July 30, 1980[57] – the date of entry into force of the Constitution of the Republic of Vanuatu of 1979.[58] The Republic is headed by the President; the legislative branch is represented by a unicameral Parliament; the executive branch is represented by the Council of Ministers, headed by the Prime Minister; the judicial system is formed by the Supreme, Appellate, village and Island courts, the Chief Justice and other judges. The model of the state structure can be characterized as hybrid, mixed: Anglo-French. Chapter 12 of the Constitution establishes the foundations of land legal relations in this State. All land in the Republic of Vanuatu belongs to the indigenous (indigenous population) and their descendants (Articles 73, 74 of the Constitution of Vanuatu), so a land dispute is resolved between the protectorates and the newly independent republic, which can own the acquired land in order to use it for public needs. The state is obliged to categorize land at the legislative level, as well as to introduce permitted types of use of land plots. The peculiarity of the Republic of Vanuatu is the assignment of all lands to the local population, this technique has long been used by the British to reserve lands in Australia and Oceania, if it was not possible to transfer them to the state or the Crown, or it was necessary to keep them in reserve to exclude the relevant land plots from trade. Since the United Kingdom is still not the only dominant Power in the Republic, the turnover of land is limited to the proclamation of land as the property of indigenous people. This makes the lands of Vanuatu inaccessible to French economically active entities in this region. The state has organized a search for minerals, since neighboring New Caledonia served as an effective example of their development, however, no hydrocarbon deposits have been discovered at present, as well as polymetallic nodules. Insignificant reserves of gold and manganese have been found on the islands, their development is not underway.[59]

Land use, land management, land valuation, quarrying and mineral prospecting are regulated by two laws: the Land Reform Act of 2014 (Land Reform (Amendment) Act No. 11 of 2014) and the Land Valuation Act of 2009 (Valuation of Land Act No. 22 of 2014). The Law on Environmental Management and Environmental Protection of the Republic of Vanuatu (Environmental Management and Conservation Act 2002), [60] The Law on Water Resources Management of the Republic of Vanuatu (Water Resources Management Act 2006), [61] and other republican regulatory legal acts: Regulations on Environmental Impact Assessment (Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations 2012), [62] National Parks Act 1993, International Trade (Fauna and Flora) Act 1989, [63] Waste Management Act 2014, [64] Pollution Control Act (Pollution (Control) Act 2013), [65] The Ozone Layer Protection Act 2010, administered by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Forestry, Fisheries and Biosecurity of the Republic of Vanuatu (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Forestry, Fisheries, and Biosecurity)[66], and Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources of the Republic of Vanuatu (Lands and Natural Resources)[67]. Vanuatu National Water Strategy for 2018 – 2030 (Vanuatu National Water Strategy 2018 - 2030).[68] The legislation on subsoil and subsoil use has not been adopted in order to restrict access to minerals. However, in the civil law of the Republic of Vanuatu there is an institution of concession, which is used as a contractual form of subsurface use, which made it possible to conduct a geological study of the subsoil of territories and water areas, ensuring the development of deposits of common minerals for the construction industry of the economy. Thus, in the Republic of Vanuatu, a regulatory legal framework and state mechanisms have been created for the protection of the environment and the exploitation of natural resources, the latter is not carried out in view of the conflict of interests between the United Kingdom and the French Republic, the solution of which is possible under the Antarctic scenario by organizing joint subsurface use of protectors with the payment of royalties to a dependent State – the Republic of Vanuatu. Republic of Fiji The Fijian Constitution (Constitution of The Republic of Fiji 2013)[69], which has been operating since September 7, 2013, receives the Westminster model of public administration, for this reason and because of the loyalty of the ruling establishment to the United Kingdom, the Republic of Fiji was re-admitted to the British Commonwealth of Nations, since until October 10, 1970, this state was under the rule of the British crown. The President of the Republic of Fiji heads the State and the executive branch, represented by the Government – Cabinet (Cabinet or a Minister), but, in fact, replaces the place previously occupied by the British Governor-General. Legislative power is concentrated in the hands of the unicameral Parliament, and judicial power includes the Supreme, Appellate Courts, as well as magistrate courts. Article 29 of the Constitution of the Republic of Fiji contains a provision confirming the inviolability of the property rights of property owners who owned it before the Constitution came into force. Property can be either public or private. However, traditional ownership is a special type of land ownership that is not alienable and belongs to the indigenous population. The exception is the seizure of traditional property by the State for public needs in a legal manner. Land that has been removed from the title of "iTaukei" (ordinary possession of the indigenous population) is subject to return to the original owner and the title of "iTaukei" if it is no longer used by the state for public purposes. Paragraphs 4 and 5 of the twenty-eighth article of the Fijian Constitution establish a special regime for the ownership of Rotuman and Banaban lands "Rotuman land" and "Banaban land", which is withdrawn from circulation and can only be used by the local indigenous population. The Republic has the right to seize land on the islands of Rotuman and Banaba for temporary use for public needs, followed by the return of the seized plots to the indigenous population. The concepts of "land leases” or “land tenancies" are used in article twenty-ninth article of the Constitution, their content is disclosed to indicate possible land transactions, including leases for subsoil use purposes. At the same time, rentiers can receive income from minerals when they are extracted from the bowels of their land or reservoir, as provided for in article 30 of the Constitution of the Republic of Fiji. The rent of the owners of land and the bottom of reservoirs from subsurface use within their property, including the bottom of the territorial sea adjacent to traditional lands, is calculated based on: the income of the subsurface user from the exploitation of the deposit; environmental damage and the costs of the subsurface user for land reclamation or compensation for environmental damage; contributions to the state environmental fund, whose funds go to compensation environmental consequences of subsurface use; costs for the administration of mineral exploration and development, costs for subsurface use; payments for the use of subsurface resources carried out by the subsurface user in favor of the Republic of Fiji. The Fair Share of Mineral Royalties Act 2018 provides for deductions to both the owner of the land plot and the state for geological exploration of the subsoil in order to search for minerals in the territory of the Republic of Fiji. The Minister of Lands and Mineral Resources (Minister for Lands and Mineral Resources) manages the land use and Subsoil use of the Republic of Fiji, the Minister for iTaukei Affairs (Minister for iTaukei Affairs) takes into account the rights of the indigenous population in the exploitation of natural resources, the Minister of Agriculture and Waterways (Minister for Agriculture and Waterways) is responsible for the development of ocean resources, the Minister Public Works, Transport and Meteorological Services (Minister for Public Works, Transport and Meteorological Services) oversees environmental monitoring, emergency management and prevention of the consequences of natural disasters, environmental disasters. The Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources of the Republic of Fiji[70] manages the State land fund, which makes up 3% of the total land area of the islands. The rest of the land is private and iTaukei. Private land is mostly leased, the register of tenants and sub-tenants is maintained by the Ministry in question.[71]

The Fiji Environmental Management Act 2005 provides for the inventory of natural resources and the adoption of a national resource management plan (article 25). The cadastre of natural resources and the national plan for their management are compiled on the basis of an inventory of natural objects. The Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources of the Republic of Fiji has a department responsible for inventory, cadastre and planning of environmental management, as well as for environmental protection activities, including on the basis of the atlas of vulnerability of coastal areas, responding to environmental offenses and natural disasters. The unit conducts environmental studies and inspects natural objects, collects geographical information and information on natural resources for the compilation of the inventory of natural resources (Article 13). The Law on Surveyors (Surveyors Act 1969) and the Regulations on Geodetic Surveys (Surveyors Regulations 2021) define the procedure for mapping and determining the boundaries of land plots, lines of urban planning regulation, technical requirements for geodetic survey methods, interpretation of field data. The boundaries of water bodies are established along the low tide line, which, in accordance with the fifth article of the Water Resources Tax Act (Water Resource Tax Act 2008), is used to determine the area of the reservoir for calculating the water tax. However, watered quarries are not water bodies and land tax is paid from them, not water, - Quarries Act 1939. The Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources of the Republic of Fiji is assisted by the Fiji National Trust, which, according to the third article of the Fiji National Trust Act (1970), is obliged to contribute to the permanent conservation of natural resources, the protection of wildlife and flora, protecting their marine habitat. At the same time, any person affected by the nature user can apply to the court with a civil claim for compensation for damage to health, property, the environment, lost profits and real damage, as provided for in article 50 of the Fiji Environmental Management Act. The Petroleum (Exploration and Exploitation) Act 1978, as well as the Maritime Transport Act or the Maritime Code of Fiji (Maritime Transport Act 2013/Fiji Maritime Code) regulate the exploration, production, and transportation of hydrocarbons, safe subsurface use in Fiji's offshore oil and gas fields. The elimination of accidents and consequences of natural disasters in the ocean, as well as pollution of the marine environment by subsoil users, is regulated by the Law on Natural Disaster Management (Natural Disaster Management Act 1998). This fully ensures the right of every Fijian to a clean and healthy environment, the protection of the natural world for the benefit of present and future generations, provided for in the fortieth article of the Constitution of the Republic of Fiji. It should be noted that the Fiji Maritime Spaces Act 1977 does not contain rules that contradict the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Regulation of the construction, maintenance and use of installations for the exploration or development of the seabed, subsurface underwater areas, protection of marine living resources, laying of underwater pipelines, cables, fisheries and navigation is implemented by the Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources of the Republic of Fiji jointly with the Fijian Minister of Public Works, Transport and Meteorological Services by virtue of the Continental Shelf Act (Continental Shelf Act 1970). Subsoil use on the continental shelf of the Republic of Fiji is carried out by Fijian organizations, as well as by foreign investors or with their participation. In order to obtain the right to use mineral resources, a foreign legal entity must be entered in the register of foreign investors in accordance with the third article of the Foreign Investment Act 1999. The concept of investment is disclosed in the Investment Act (Investment Act 2021). The Petroleum (Exploration and Exploitation) Act 1978 provides for the admission to oil and gas fields of both Fijian legal entities and foreign, as well as joint ventures. The Ministry of Lands and Mineral Resources accepts applications from subsurface users for licensing exploration, mining (permission to operate a mining enterprise on islands), offshore production (permission to operate a raw material enterprise at sea), laying and using an offshore pipeline, oil transmission through a pipeline, for which it charges appropriate payments from subsurface users. The Law on Oil Exploration and Development (Article 49) provides for the accounting of production licenses (Record of Production Licenses) and pipeline licenses (Record of Pipeline Licenses). Transport licenses for the "sea route" are registered separately. Licenses for marine subsurface use (combined licenses for the search for minerals and their extraction) are issued for a period of 21 years with the possibility of extension for 5 years (Article 18). The license for the pipeline is issued for the duration of the construction project, and then for the period of transfer of hydrocarbons through it, is extended by the Minister when submitting the relevant application to him no later than 6 months before the expiration of the current permit. The validity periods of pipeline licenses and the terms of their extension are determined individually based on economic needs. Subsurface use on the islands is licensed by the same ministry under the same conditions as in the marine environment, but the terms of subsurface use are determined by the type of mineral, that is, they are differentiated. Mainly, gold and accompanying silver are mined in Fiji. Regulatory legal acts regulating subsurface use are contained in a special register of officially published documents.[72] The abundance of natural resources of the Republic of Fiji caused the unsuccessful attempts of the ruling elite to free themselves from the British protectorate and independently administer the natural resources of the republic, which still came under the control of the United Kingdom as a resource donor to the Australian Union, the People's Republic of China and the Republic of Indonesia, as well as Japan. Consequently, the geopolitical position of the Pacific states affects the intensity of exploitation of their natural resources: the closer to the Asian region, the more intensive the use of the natural resources of the islands and waters by the Anglo-Saxon coalition in order to extract economic benefits, priority exhaustion near Asian areas due to the risk of their transition to the control of the People's Republic of China and other countries claiming to these resource bases. Solomon Islands

The statehood of the Solomon Islands[73] is based on the Constitution (The Constitution of Solomon Islands 1978)[74] as amended in 2022.[75] However, after the declaration of independence from the United Kingdom, the monarch of England, represented by the Governor-General, became the head of the Solomon Islands.[76] Executive branch – the Government consists of the Governor-General and the Cabinet, headed by the Prime Minister and including other ministers appointed from among the members of the unicameral Parliament (National Parliament of Solomon Islands). Until the adoption by this body of laws replacing the normative legal acts of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, British laws are in force in the jurisdiction of the Solomon Islands, and justice is administered under common English law. The High Court of the Solomon Islands, the Chief Judge, the Court of Appeal of the Solomon Islands, the District Court of the capital City of Honiara and the equivalent district (provincial) courts, as well as the Solomon Islands Land Court exercise judicial power. Consequently, the state apparatus is built on the principles of the Westminster system of government. Articles 110 – 113 of the Constitution of the Solomon Islands [77] provides for unlimited ownership of land for residents of this state, meaning, within the meaning of articles 20 – 26 of this document, its citizens and Britons living on the islands. Land may be in public and private ownership. Since the Solomon Islands is a unitary State, the lands of the districts are State, not municipal property. According to the constitution, lands have a general regime, therefore, the Solomon Islands have moved away from traditional ownership, however, the legislator can return such – ordinary (traditional) ownership of land, assign the corresponding right indefinitely to a specific owner or to an indigenous community, as well as cancel the relevant normative legal acts on traditional land. The seizure of any land is allowed by the Constitution only on legal grounds with prior proportionate and fair monetary compensation to the owner of the land plot and only after unsuccessful negotiations with him on the voluntary alienation of immovable property under the contract. The Cabinet includes 21 ministries and the Office of the Prime Minister.[78] Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock)[79] manages land through the Department of Agricultural Planning and Land Use, and is also responsible for cartography conducted by the Geographic Information System group. The Biosecurity Department[80] of this ministry, in accordance with the Biosecurity Act 2013, fights pests and diseases. Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, Disaster Management and Meteorology (Ministry of Environment Climate Change Disaster Management and Meteorology)[81] acts as the operator of several laws: The Environment Act 1998, the Wild Life Protection and Management Act 1998, the Protected Areas Act 2010, the Meteorology Act 1985, the National Council Act on Natural Disasters (National Disaster Council Act 1989) and others. The main tasks of the Ministry are environmental conservation, meteorology, environmental monitoring and disaster management. The Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources[82] not only issues fishing licenses, but also coordinates and controls the use of all marine natural resources. The Ministry of Forestry and Research (Ministry of Forestry and Research) is guided by the Forest Resources and Timber Utilization Act (Forest Resources and Timber Utilization Act) in order to implement a program for the development of forests and reforestation, forest resources management, transfer of forest plots for use, licensing of logging, processing and export of products of the forest industry. The Ministry of Lands, Housing and Survey (Ministry of Lands, Housing and Survey) implements land reform for the transition from communal lands to ordinary civil circulation while preserving traditional land ownership, is responsible for urban planning, land valuation, cadastral system and land accounting, geographical maps, land management and land fund management. This Ministry oversees land transactions, including leases and subleases, registers land transactions and ensures timely lease payments. Land transactions are made in written electronic form, as well as the conclusion of lease agreements (subleases), through the website of the Government of the Solomon Islands. Payment under contracts of sale, barter, donation, lease, sublease and others with invoicing is carried out through the same government website, which provides financial monitoring, control over business activities and proper accounting of individuals at their place of residence and place of their stay. [83] The site allows you to register real estate rights, get access to registry books, cadastral plans, real estate registry, registration books of land transactions, renew existing contracts and a construction license obtained through the government website. Similar experience of the Solomon Islands can be adopted by the Russian Federation, including in terms of obtaining electronic licenses for the right to use mineral resources through https://solomons.gov.sb /. The Ministry of Mining, Energy and Rural Electrification (The Ministry of Mines, Energy & Rural Electrification) implements the National Mineral Policy [84] and the Declaration on Water Resources Management (Water Governance Awareness)[85]. This ministry consists of five departments: · Geological Survey Division, which deals with geological exploration, mapping, geochemistry, seismology and petrology; · Department of Mines (Mines Division), supervising the mining industry, carrying out industrial supervision, including during the construction of buildings, responsible for the economic efficiency of subsurface use; · Department of Water Resources (Water Resources Division) responsible for drilling wells, water management and hydrology;

· Petroleum Department (Petroleum Division), responsible for the management of the hydro-carbon economy and oil and gas activities; · Department of Energy (Energy Division), responsible for energy conservation and energy efficiency, protection of the ozone layer from harmful emissions into the atmosphere, renewable energy sources, oil and gas complex and electric power industry. In addition, the resource sector is represented by state-owned companies: energy[86] and water management[87]. The Ministry of Mining, Energy and Electrification of Rural Areas interacts with customs, the diplomatic department, the Republican Audit Service, the Ministry of Industry and Trade, and other executive authorities involved in the implementation of state policies in the field of environmental management.[88] The Ministry of Mining, Energy and Electrification of Rural Areas issues a license to search for minerals and precious metals on the basis of an electronic application in the prescribed form[89]. The exploration license [90] begins to be issued by the Ministry after payment of the established license fees to the Treasury under the Ministry of Finance. The applicant must confirm the sufficiency of financial resources, technical competence to conduct effective intelligence work, as well as the viability of the search program. The Director of the Department of Mines considers the application of a potential subsoil user and, if the submitted document meets the formal criteria, submits it to the Council of Mining and Minerals for decision-making (Miners and Mineral Board).[91] On the basis of Article 11 of the Law on Subsoil and Subsoil Use (Mines and Minerals Act)[92] all projects of licenses for exploration (Prospecting Licenses) and mining (Mining Leases) of minerals, lease of mine workings, for the production of construction materials, licenses for the operation of special land plots and subsoil plots, licenses for access to roads, as well as gold trading licenses are reviewed and approved by the Mining and Minerals Council prior to the issuance of appropriate licenses or permits by the Minister of Mining of the Solomon Islands.[93] A license for mining is also issued on the basis of an electronic application.[94] Having received an application for geological exploration, the Miners and Mineral Board may approve the issuance of a license, reject the application or announce a tender for the right to use the subsoil of the requested search area. The Minister of Mining, Energy and Rural Electrification notifies the Prosecutor General of the issuance of a prospecting license for a subsoil plot, and the Director of the Mines Department notifies the applicant of the decision. After that, the applicant agrees with all landowners on the use of their plots for geological exploration, concludes contracts with them on payment for the use of land plots for conducting mineral prospecting within their borders. The specified Ministry is obliged to provide administrative support to the subsoil user to resolve disputes with landowners of the territory where geological exploration of the subsoil is allowed. Landowners who disagree with the civil conditions of exploitation of their lands by the subsoil user, instead of contractual payments, land rent is paid in a public legal manner to the accounts opened to the relevant landowners in the credit institution by the Department of Mines, in the amount determined by the ministry, which is considered sufficient to compensate the subsoil user for the use of someone else's land for the purposes of geological exploration of the subsoil. We propose to use the above experience of the Solomon Islands in the Russian Federation. After agreeing with the owners of the lands to use their plots for subsurface use under civil legal agreements, as well as the obligation in public legal order of persons who have not concluded these contracts with the subsurface user to provide land for exploration on a reimbursable basis, a copy of the prospecting license - Prospecting Licenses – is sent to the provinces within which the license area is located. The license is issued by the Ministry for the period required by the subsoil user, defined in the license itself, which we have already met in the Kingdom of Tonga.[95] The Minister of Mining, Energy and Electrification of Rural Areas not only oversees the use of subsoil within the framework of the issued license in accordance with the conditions specified therein, but also extends the use of subsoil for an economically justified and necessary period for the license holder. Such a legally fixed practice can be used in the Russian Federation. A feature of the legislation of the Solomon Islands[96] is the declarative procedure for environmental damage. The subsoil user pays for the environmental impact assessment himself, compensates for the damage caused to the owner of the land plot and the state, pays for the costs of land reclamation and restoration of nature by the contractor hired by him, or does it independently and at his own expense. The Ministry and the affected landowners are informed about the restoration of the natural environment damaged during the study of the subsoil in the form. Administrative and criminal liability of subsoil users occurs only if they evade compliance with the civil law compensatory mechanism. We propose to use a similar scheme of compensation for environmental damage by subsoil users in the Russian Federation.

Mining is carried out on the basis of an application for the right to use the subsoil on the basis of a lease or mining license.[97] A lease or mining license is granted by the Ministry of Mining, Energy and Rural Electrification of the Solomon Islands in the same manner as a prospecting and exploration license. Thus, the right to use mineral resources on the territory of the islands is granted in a uniform manner on the basis of four types of licenses: first, search, second, exploration; third, mining; fourth, rental. In addition, there is an alluvial license issued by the Department of Mines to any citizen of the Solomon Islands over the age of 21 for the extraction of loose gold on his land plot or the land plot of the province where this person owns the land, for a period of up to 1 year with the possibility of extension for no longer than the same period. If the applicant is not a landowner in a particular province, then alluvial mining is possible only within the boundaries of the plots of owners who have given alluvial permission. Without the consent of the owner, alluvial extraction is not possible, except for the owners of the lands of the relevant province by virtue of the law. Other subjects of the right to use subsurface resources, except for alluvial ones, can only be legal entities, including foreign investors, for whom the most favored nation regime has been introduced by the Solomon Islands, a register of foreign investors is maintained, their admission to subsurface use is carried out in a general manner.[98] It should be noted that the antimonopoly legislation limits the share of one individual in a subsoil user organization to five percent and does not allow such a person to own legal entities participating in a subsoil user company by more than five percent. This minimizes the risk of concentration of income from the exploitation of natural resources in one hand or in the hands of a narrow group of persons, which does not prevent the use of front (trusted) individuals for the registration of commercial companies in order to evade antitrust requirements with the resulting legal, economic and managerial risks. Subsurface users under an alluvial license have the right to sell the gold they have extracted only to holders of a Gold Dealer's License. We propose to apply alluvial licensing in certain regions of the Russian Federation. The Ministry of Mining, Energy and Rural Electrification issues licenses for geological exploration – Petroleum Prospecting License and development (oil production) – Petroleum Development License in the waters of the Solomon Islands in accordance with the recommendations of the Petroleum Advisory Board.[99] Meanwhile, the turnover of oil and gas resources is controlled by issuing licenses for the possession of hydrocarbons (License to Possess Petroleum). Licensing of offshore oil activities is carried out in electronic form and is described on the website of the relevant ministry.[100] Having familiarized with the experience of licensing the subsoil use of the Solomon Islands in order to achieve transparency of administrative procedures, competitiveness of Russian oil and gas production, economic efficiency of the domestic fuel and energy complex, we propose the Russian Federation to borrow the experience of the Solomon Islands in terms of the transition of granting the right to use the subsoil and other permissive administrative procedures carried out by public authorities in electronic form, leveling the corruption factor and minimizing the time spent on the execution of administrative regulations, therefore, reducing the burden on civil servants and budget expenditures on the organization of the work of the state mechanism. Republic of Nauru Nauru (Republic of Nauru)[101] is a Pacific state in which the period of colonization by the British was replaced by a German protectorate, followed by joint administration by the Australian Union, New Zealand and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland following the results of World War II on the basis of a mandate from the League of Nations, and then the United Nations. The formal independence of the mandated Republic of Nauru was proclaimed on January 31, 1968, but in fact this state still remains economically and politically dependent on the Commonwealth of Australia. The President of Nauru is elected by the unicameral Parliament from among its members, the Speaker of the Parliament and his Deputy (Deputy Speaker) cannot be candidates for the post of head of state. Executive power is exercised by the Cabinet [102], headed by the President of the Republic and including ministers appointed by the Head of State from among the members of Parliament (Parliament of Nauru), consisting of 18 people elected by the citizens of this country. The judiciary is represented by the Supreme Court of the Republic of Nauru, the Court of Appeal, and fourteen district courts (articles 16 – 57 of the Constitution of Nauru). Consequently, Nauru, as a member of the British Commonwealth of Nations, implements the Westminster model of public administration. [103] The Ministry of Environmental Management and Agriculture (Department of Environment Management and Agriculture) and the Ministry of Land Management (Department for Land Management) implement the state policy in the field of environmental management.[104] At the beginning of the XIX century, industrial extraction of phosphates began in Nauru, the deposits of which are currently being depleted, the reserves will last for about two decades at the current rate of quarrying. The Pacific Phosphate Company, formed in 1902 as a result of the merger of South Pacific Company Ltd and Jaluit Gesellschaft, received exclusive rights to extract phosphates on the territory of the colony of Nauru, having an Australian domicile, works to this day as the only subsoil user in the island part of the Republic of Nauru.[105] The right to use the subsoil of this company is granted under English law, the applicable law in resolving disputes with Pacific Phosphate Company is the common law of the United Kingdom. That is why the Republic of Nauru accused the Commonwealth of Australia of state protectionism and appealed to the International Court of Justice of the United Nations to recover compensation from Australia for damage to land caused by an Australian subsoil user who received the exclusive right to develop phosphates on the island during the protectorate, confirmed during the mandatory period, on unfavorable conditions for the Republic of Nauru, including without land reclamation spent mines. Compact of Settlement concluded the international dispute between the States with the payment of 107,000,000 Australian dollars to the Republic of Nauru by the Commonwealth of Australia.[106]