|

DOI: 10.7256/2454-0595.2023.2.40851

EDN: GNXJXZ

Received:

27-05-2023

Published:

06-06-2023

Abstract:

The object of the study is the relations of nature management in the Polynesian States, the subject is the legislation and doctrine in the field of exploitation of natural resources of the Polynesian countries: the United States of America (Hawaii, American Samoa, unincorporated territories), the Kingdom of New Zealand (Cook Islands, Niu, Tokelau), the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (Pitcairn Islands), an Independent State Samoa, the Republic of Kiribati, the Kingdom of Tonga, the Kingdom of Tuvalu, the French Republic (French Polynesia, Wallis and Futuna), the Republic of Chile (Isla de Pasqua and Juan Fernandez). The author examines the features of the state natural resource apparatus in various jurisdictions, first of all, the management of the environment and subsoil use by executive authorities. The article examines the institution of ownership of land and subsoil, the permissive procedure for the use of natural objects. In addition to the traditional, the researcher identifies a new type of property – family ownership of land, distinguishing it from communal, tribal and ancestral, and also draws attention to the inequality of ownership forms and discrimination in this area by the English crown of formally independent states and their citizens. The work is a new round in the theory of natural resource law of foreign countries, the relevance of the research is due to the theoretical and practical significance of the content of the article, which reflects domestic economic interests in Oceania. The scientific novelty of the presented work lies in the originality of the conclusions and the work itself, which contains fundamentally new information on the subject of research. This is one of the few scientific publications in the World on the natural resource law of the Polynesian States. The author discusses with foreign scientists, analyzing foreign doctrine and legislation. At the same time, violations are noted in the implementation and implementation of the norms of international maritime law in the Pacific Ocean; the creation by the collective West of natural resource reserves, regulatory legal bases and state mechanisms for the exploitation of the Polynesian environment in case of need (economic need and (or) global conflict).

Keywords:

land Ownership, Subsoil Ownership, Natural Resource Law, Continental Shelf, International Maritime Law, Polynesia, Polymetallic Nodules, Polynesian Subsoil Use Management, Pacific Ocean, Land Court

This article is automatically translated.

You can find original text of the article here.

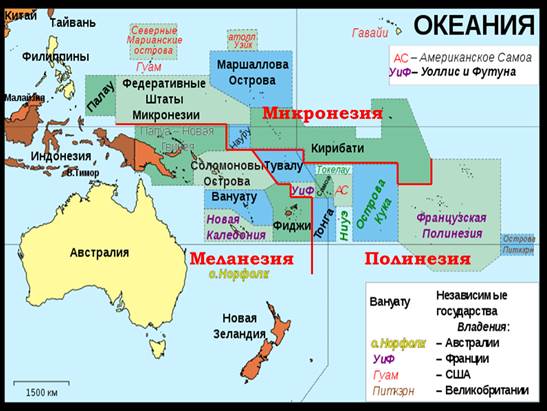

In 1831, captain of the French Navy Jules Sebastien Cesar Dumont-Durville (fr. Jules S?bastien C?sar Dumont d'Urville), an explorer of Oceania [1], proposed to divide this part of the world, located in the Pacific Ocean, into three regions: Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia. [2] The scientist's report and the maps presented by him became the basis for the colonization of the respective territories by the maritime powers. [3] The concept of "Polynesia" was introduced into scientific circulation earlier – in 1756 by Charles de Bross (fr. Charles de Brosses) to denote the multitude of all the islands and atolls of Oceania, it is composed of two ancient Greek roots: "" - "many", "V" - "island". [4] The scientific community accepted Dumont-Durville's proposal, so Polynesia acquired its modern borders.[5]

Polynesia today includes the territories and waters of nine States (the United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, New Zealand, the Republic of Chile, the French Republic, the Republic of Kiribati, the Independent State of Samoa, the Kingdom of Tonga, Tuvalu), dependent State entities and the external territories of some of them. [6] The legal regime of States whose external territories are located in the study area requires a separate study, with the exception of regional specifics. [7] The purpose of our study is to identify the features of the legal regulation of subsoil use in Polynesian jurisdictions. To achieve this goal, it is necessary to solve the main tasks: to study the normative legal acts regulating the relations of subsoil use in Polynesia, as well as the relevant doctrine, presenting their analysis to the reader. Following the recommendation of the publishing house, we have chosen the regional principle of presenting the scientific material presented to the reader of the study. United States of America The legal regime of subsurface use in the United States of America is discussed in detail in one of the recent publications of the publishing house. [8] Only one American state is located in Polynesia – Hawaii. It is with him that we should begin our narrative about the legal formalization of Polynesian nature management and management of subsurface resources. Hawaii The Department of Land and Natural Resources of the State of Hawaii (Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources) [9] is a regional authority for the management of natural resources within the authority of an American entity consists of 14 structural divisions: firstly, the Department of Boating and Ocean Recreation (Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation) [10] is responsible for recreation programs on the coast and in the ocean, controls 21 state harbors (the rest are private), 54 launching ramps, 13 sea berths that can be used for the purposes of marine subsoil use, as well as 10 ocean water areas (environmental monitoring) and 108 recreational ocean zones; secondly, the Bureau (department) of transportation (Bureau of Conveyances) [11] is engaged in cartography, microfilming of documents and accounting of rights to real estate; thirdly, the Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands (Office of Conservation and Coastal Lands) [12] - oversees more than two million acres of land in public and private ownership located within the State protected Land use District, controls the protected area, as well as beaches and marine lands outside jurisdiction of the state of Hawaii towards the ocean; Fourth, the Division of Aquatic Resources [13] - manages water resources (freshwater and oceanic), implements aquaculture and commercial fishing programs, issues fishing licenses, protects marine flora and fauna, is responsible for the use of the marine environment in accordance with the interests of the state; Fifthly, the Division of Conservation and Resources Enforcement [14] - monitors compliance with the land and natural resource legislation of the state of Hawaii, as well as by-laws of its authorities, oversees the exploitation of lands and protected natural areas of the state (parks, historical sites, forest, river and marine reserves areas, coastal zones and coasts of the state), aquatic life and wildlife, trafficking in firearms and ammunition, performing functions delegated by the police – performs a law enforcement function; Sixth, the Engineering Division [15] - provides engineering support to the Department of Land and Natural Resources of the State of Hawaii and its structural divisions, conducts projects for the repair and overhaul of environmental infrastructure, is responsible for the maintenance of environmental activities, programs for the development of water and land resources, minerals, ensures the prevention of natural disasters; Seventh, the Division of Forestry and Wildlife [16] manages state forests, natural territories, public hunting grounds, controls commercial forestry and hunting, licenses hunters; eighth, the Department of Preservation of historical Heritage (State Historic Preservation) [17] - works in the directions of three sub–departments (departments): the first is history and culture, the second is archeology; the third is architecture;

ninth, the Land Division [18] manages land use and implements the plans of the State of Hawaii for the development of public lands (public lands that are not under the jurisdiction of other state bodies and organizations are administered by the Land Department of the Department of Land and Natural Resources of the State of Hawaii), in addition, the department performs the functions of registering all regulatory legal acts in the field of nature management, and is also an archive of documents in the field of exploitation of the natural environment; tenth, the Department of State Parks (Division of State Parks) [19] - manages fifty state parks on an approximate area of 25,000 acres of land, issues camping permits; and the other four departments – the Office of the Chairman (Office of the Chairman); the Office of Administrative Services (Administrative Services Office); the Human Resources Department (Personnel Office); Communications Department – Press Service (Communications Office). The Department of Land and Natural Resources of the State of Hawaii operates on the basis of administrative regulations (Department of Land and Natural Resources, Hawai'i Administrative Rules, Title 13).[20] The regulations of the named department are adopted and revised in whole or in part on the basis and in accordance with the procedure provided for in Chapter 91 of the Charter of the State of Hawaii (Hawaii Statute). [21] Amendments to the rules of work are developed and proposed by the department itself for preliminary approval by the Board of Land and Natural Resources [22] and the Office of the Attorney General of the United States of America for the State of Hawaii (Hawai Department of the Attorney General). After preliminary consideration, the amendments are sent for public discussion, and at the end of the public hearings and the comments expressed on them, the draft is finally approved by the Land and Natural Resources Council and the Attorney General of the State of Hawaii. The approved draft amendments are submitted to the Governor of the State of Hawaii for signature and enter into force after the text signed by the head of the state is deposited with the depository – the Vice Governor of Hawaii. The Land and Natural Resources Council is the highest executive collegial body of the natural resources management of the State of Hawaii consists of seven members: the Chairman (Executive Director of the Department of Land and Natural Resources of the State of Hawaii) and two other exempt members appointed by the Governor of Hawaii after approval of candidates with the Senate of this state for a four–year term of office, while the council cannot enter more than three representatives of the same party. The remaining members of the council represent four districts of the state of Hawaii - Oahu, Hawaii, Maui Nui, Kauai (O'ahu, Hawai'i Island, Maui Nui, Kaua'i), are empowered by representative bodies of Hawaiian districts for four years. The Council, as a rule, meets once every two months, unless there are exceptional cases for holding a meeting. Another environmental management authority in Hawaii is the Commission on Water Resource Management (Commission on Water Resource Management). [23] It consists of seven members: the chairman of this commission ex officio is the chairman of the Council on Land and Natural Resources, the deputy is the Director of the Department of Health of Hawaii (Director of the State Department of Health). The other five members of the commission are appointed by the Hawaii State Senate for a four-year term of office on the recommendation of the Governor of Hawaii. The Commission meets at least once a month, if there is no exceptional situation, work in its composition is carried out free of charge. The Commission is guided in its activities by the Water Code of the State of Hawaii (State Water Code). [24] The Law on Environmental Protection of Hawaii (Hawaii Environmental Response Law) [25] establishes the rules of environmental protection of the state and response to pollution of natural objects, defines responsibility for environmental offenses. The Law on the Environmental Policy of Hawaii (Hawaii Environmental Policy Act) [26] is the basic among the regulatory legal acts of the region regulating environmental requirements. It is developed by the Hawaiian laws on clean air; on clean water; as well as on safe drinking water; on complex environmental impact and compensatory liability; on endangered species; on conservation and restoration of resources; on underground storage tanks; on control of toxic substances; on insecticides, fungicides and rodenticides and others. Note that there is no special legislation regulating industrial subsoil use in this region, including in the marine environment. This means that the United States of America does not intend in the medium term to use minerals lying primarily in the Hawaiian oceanic waters, that is, to develop offshore deposits. The state of Hawaii is mainly of recreational importance and, most likely, these natural properties of the region will be used in the future, which determines high-quality and conscientious environmental protection. The level of environmental offenses in the state of Hawaii is very low, only one incident is known in history that led to pollution of the marine environment of the region. The United States of America will strive to preserve the minerals of the state of Hawaii, as well as its other Polynesian territories, as a strategic reserve, which from national sources of natural raw materials will be used last. Such a position of the American administration allows us to draw a conclusion by analogy: other Polynesian states and dependent territories will also not be used by them as a source of mineral raw materials in the foreseeable future. The minerals of Polynesia in the waters controlled by the United States of America will become a material reserve for future generations of Americans or will serve their current generations in the event of a global armed conflict with an embargo or the inability to supply the necessary raw materials to North America. American Samoa

The United States of America exercises State sovereignty over its unincorporated Territory – American Samoa. [27] State power in this territory has been exercised by the American President since 1900 through the delegation of relevant powers, currently, to the Office of Insular Affairs of the United States Department of the Interior (Office of Insular Affairs of The United States Department of the Interior), until 1956 these powers were delegated to the American Navy (U.S. Navy). [28] American Samoan citizens are American citizens, but do not participate in metropolitan elections and do not pay federal taxes. The Territory has its own representative in the U.S. House of Representatives without the right to vote. The Constitution of American Samoa provides for the separation of powers, where the executive power of the Territory is represented by the Governor (Governor of American Samoa) and the Government of the Islands (Government of American Samoa); legislative power – bicameral Parliament – Legislature (Legislature of American Samoa), consisting of the House of Representatives (House of Representatives) and the Senate (Senate); judicial – The Supreme Court of American Samoa and the District courts. [29] At the same time, Samoan laws cannot contradict American ones, as well as international treaties of the United States of America. The Government of American Samoa consists of fifteen bodies, but only two of them directly provide environmental management. First of all, this is the Territorial Energy Office of the American Samoa Government, which is subordinate to the U.S. Department of Energy and administers the finances allocated by the United States for energy. The Department is formed by the Governor of the Territory and the US Secretary of Energy, it is responsible for energy-efficient and energy-saving technologies, the introduction of alternative fuels, renewable energy programs.[30] Another body is the Department of Marine and Wildlife Resources of American Samoa (American Samoa Department of Marine and Wildlife Resources) [31] dealing with the protection of the marine environment, monitoring and prevention of emergencies in the ocean, cartography, ecosystems and plans for the development of water areas, environmental economics and environmental protection financing. An analysis of the territorial administration of American Samoa, the economy of the region and the structure of export-import relations indicates the presence in the waters of the islands and on their territory of a significant amount of natural resources, including minerals, the use of which is not carried out, except for scientific and recreational purposes, transport infrastructure and industrial tuna fishing. Unincorporated territories United States of America [32] The study of the Pacific Ocean allows us to assert the presence in the Polynesian waters of seven territories not incorporated into the United States of America [33], state sovereignty over which is exercised by the United States of America. These include Baker Island; territories of the Central Polynesian Sporadic Islands from the Line Islands group: Kingman Reef, Palmyra Atoll, Jarvis Island; Johnston Atoll; Midway A toll Islands; Howland Island and other territories. These Pacific islands are not officially inhabited, but they have berths, including for large ships, airfield strips, stocks of aviation and ship fuel, lighthouses and other infrastructure facilities. Access to the listed unincorporated American territories is granted only to scientists with the permission of the Office of Island Affairs of the United States Department of the Interior. Some of them are used for nuclear testing, processing and storage of chemical weapons, and the study of biological organisms. Thus, the island infrastructure indicates the placement of military bases and military facilities of the United States of America on unincorporated territories. The exploitation of natural resources of the territories under consideration by individuals and legal entities is not carried out, with the exception of the completed short-term operation of the Kingman Reef for open-pit guano extraction. However, all these American territories have a special legal regime - and this is not even a legal fiction, but a legal paradox: the United States of America does not include these territories in its composition (does not recognize them included within its state borders); at the same time, it declares the exercise of state sovereignty over them, direct subordination to the President of the United States, powers the management of the relevant islands is delegated to the U.S. Department of the Interior; proclaim the regime of a 12-mile maritime zone outside the internal sea waters equivalent to the regime of the territorial sea of the United States of America; declare the presence of the continental shelf of the United States of America around these territories within 200 nautical miles from the baselines that are the internal boundary of the territorial sea that does not constitute the American water area. Of course, the regime of the internal sea waters of the studied islands is declared. The United States of America proclaims the existence of their two-hundred-mile exclusive economic zone around the relevant unincorporated American territories. Such a phenomenon in international maritime law is a flagrant violation of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. [34] The United States of America extends de jure the provisions of national American legislation and international treaties, including the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, not only to the territory or waters of this State, but also to the territories and waters that they own de facto and do not de jure include in the country. Consequently, the legal regime of subsurface use established in the United States applies to controlled territories. In relation to them, the Americans have established a regime of nature protection zones, which makes it possible to withdraw unincorporated territories from economically active areas, reserving them for their future generations. Kingdom of New Zealand

The legal regime of subsurface use in New Zealand is discussed in detail in one of the recent publications of the publishing house. [35] At the same time, it does not affect the New Zealand territories in Polynesia: Cook Islands, Niue and Tokelau. Subsoil use in these areas, as stated in the designated article, is carried out according to the national legislation of these States, headed by the sovereign of New Zealand, which forms with the named subjects of international law a state not recognized by the international community – the Kingdom of New Zealand, headed by the English monarch. Cook Islands The Cook Islands, a self–governing Territory in free association with New Zealand, are recognized by 48 countries (have diplomatic relations), as well as the European Union as an international organization. The King of the Cook Islands – ex officio – English, and as a consequence, the New Zealand monarch, on the basis of the island Constitution of 1965 [36] is the head of state, represented by the Governor-General of New Zealand, exercising his powers through the High Commissioner of the Cook Islands (High Commissioner of the Cook Islands). The Sovereign on matters of defense and security, foreign relations, representing the Cook Islands, consults with the Prime Ministers of New Zealand and the Cook Islands, whose subjects do not have British or New Zealand citizenship. Otherwise, the territory in question is managed according to the standards of the Westminster system described in other works. The economic plan of the Cook Islands does not include subsurface use and processing of minerals, [37] despite the presence in the exclusive economic zone of significant industrial reserves of ferrous-manganese nodules and cobalt – the reserve of the English crown. The nature management of this New Zealand territory consists in the cultivation of bananas, coconuts and some other plants, fishing and shellfish farming are of great importance. The Office of the Prime Minister of the Cook Islands (Office of the Prime Minister) is engaged in monitoring and maintenance of the renewable energy project. [38] Any research in the Cook Islands, including geological exploration of the subsurface, from May 2022 can be carried out with the approval of the National Research Council (National Research Council), issued on the basis of a risk-based approach. [39] The Cook Islands Cabinet currently consists of the Prime Minister, his Deputy and four Ministers of the Crown. The Cabinet oversees energy, environmental services and disaster prevention. [40] The Self-governing Territory consumes 974 barrels of imported oil per day, fully providing its own electricity consumption within 31 megawatts/hours per day. [41] The protection of the nature of the islands is carried out on the basis of the Environment Act 2003, with the peculiarities of environmental protection of the province of Rarotonga (Rarotonga Environment Act 1994 -1995), which replaced the island Law of 1915 (Cook Islands Act 1915), which determined the order of land use, water use and environmental management. The Laws on the Territorial Sea and Exclusive Economic Zone (Territorial Sea and Exclusive Economic Zone Act 1977) and on Marine Resources (Marine Resources Act 2005), which are governed by the Ministry of Marine Resources (Ministry of Marine Resources) [42], acting on the basis of the law on this authority (Ministry of Marine Resources Act 1984), regulate the regime of commercial aquaculture, protected, among other things, by special laws - Biosecurity Act 2008 and Prevention of Marine Pollution Act 1998. But only the Law on Seabed Minerals (Seabed Minerals Act 2019) [43] is directly related to subsurface use, it regulates the exploitation of polymetallic nodules in the exclusive economic zone. [44] The first phase of subsurface use in this case is the study of the seabed, including data collection: mapping, sampling, engineering and economic modeling, environmental impact assessment of the proposed method of mining. [45] For these operations, a Prospecting Permit is issued for the period specified in the subsoil user's application. Upon completion of the exploration of the seabed minerals, public hearings are held, a report on the environmental impact assessment of the mining project is approved, after which the Ministry of Marine Resources issues a permit for an environmental project, without which it is impossible to apply for a license for commercial mining of the seabed. Such a license is granted by the Ministerial licensing commission for a period of up to thirty years with the possibility of a two-time extension for no more than 10 years each. Currently, only three such mining licenses (Exploration Licenses) have been issued in the Cook Islands, and there is not a single valid permit for exploration of seabed minerals. [46] Despite the fact that licenses and permits for subsurface use in the waters are issued by the Ministry of Marine Resources, the decision of the ministerial commission on granting the right to use the subsoil of the seabed is approved by the Cabinet of Ministers of the Cook Islands. This takes into account the positions of the Ministry of Transport, which is responsible for the prevention and elimination of accidents in the marine environment; the Ministry of Finance and Economic Management, which is responsible for taxation of subsurface use, collection of royalties, deductions of subsurface users to the welfare fund, accumulating funds for further development of subsurface use. [47] The issuance of a mining license is impossible without a positive conclusion of the National Environmental Council, which issues two types of approvals: firstly, environmental permits; secondly, permits for the implementation of environmental projects - project permits. The type of permit depends on the scale of the proposed project. The National Environment Service of the Cook Islands monitors the environment and controls (together with the Maritime Ministry) the implementation of projects of subsoil users, carries out environmental supervision, gives the National Environment Council an opinion on the possibility or impossibility of exploitation of the subsoil of the seabed, attached to the relevant environmental or project conclusion.

Niue Niue is a self–governing territory in free association with New Zealand – recognized by 18 countries (has diplomatic relations), as well as the European Union as an international organization. The King of Niue – ex officio – English, and as a consequence, the New Zealand monarch, on the basis of the Constitutional Act of 1974 (Niue Constitution Act 1974) [48] is the head of state, represented in Niue by the Governor-General of New Zealand. The Territory implements the Westminster management model. The Government of Niue consists of four members: the Prime Minister and three ministers elected by the unicameral Parliament - the Assembly of Niue (Niue Assembly) from among its twenty parliamentarians. The High, Appellate and Magistrate courts consider criminal, administrative and civil cases, being courts of general jurisdiction, with the exception of land. The Niue Land Court, whose decisions can be appealed to the Niue Land Court of Appeal, administers justice in land and other environmental matters on the basis of paragraphs 40 to 42 of the Constitutional Act of Niue, [49] guided by the Rules of the Land Court of 1969 (Land Court Rules 1969).[50] Thus, the protection of land rights and the environment, the implementation of special land rights of the crown and the indigenous population, is carried out according to the New Zealand scheme - through specialized justice. The highest court in land cases is the Land Division of the Niue High Court (High Court of Niue), which is essentially a cassation instance, while criminal and civil cases considered by the High Court are appealed to the Niue Court of Appeal (Court of Appeal of Niue), which is both an appellate and cassation instance for the Criminal and Civil Collegiums of the Niue High Court. Administrative cases of nature users and cases arising from administrative legal relations in the field of the environment are considered by the land justice system according to the rules of the relevant legal proceedings. The Government of the Self-Governing New Zealand Territory consists of three ministries, including the Ministry of Natural Resources [51], which includes three structural divisions in the areas of work: firstly, agriculture, forests and fisheries; secondly, environmental protection; thirdly, the meteorological service. The lands are under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Social Services, and the waters are under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Infrastructure. Consequently, all ministers under the leadership of the Prime Minister are engaged in the management of the environment on the distribution of powers. Niue has similar environmental legislation as the Cook Islands,[52] this follows from a review of the natural resource and environmental legislation of this Territory. [53] At the same time, subsurface use is regulated by the fifth section of the Law on the Continental Shelf (Continental Shelf Act 1964) and the Mining Act 1977, the main environmental act is the Environmental Act 2015. However, mining, except for common minerals, is not conducted in Niue. Tokelau Tokelau is an island, inland waters, territorial sea and other areas belonging to Tokelau under international law (article 1 of the Constitution of Tokelau). [54] The General Fono (the highest state body) exercises legislative power, as well as executive power, including in the management of natural resources and the environment. The Council of the Government of Tokelau, in between sessions of the General Fono, implements its decisions in the field of ecology and nature management. On the basis of article 15 of the Constitution of Tokelau, land turnover is controlled by the taupulegi – councils of village elders, while no land plot can be owned by a person who is not a Takeluan. Lands are divided into ordinary (traditional) – owned in accordance with village customs (traditions); and special – transferred to ownership on other (special) grounds. Land disputes in Tokelau are settled by the High Court of Tokelau under Common English Law. Tokelau can use the land of villages or other owners only on the basis of a contract, the use of the land of an individual in the absence of his consent to the transfer of land for public use is possible after paying him fair and proportionate compensation for the withdrawal of the necessary land. The Constitution of Tokelau, in force since 1948 in connection with the repeal of the Law of New Zealand "On Tokelau" (Law of Tokelau), and adopted by popular vote, contains a reference to the Treaty of Free Association with New Zealand (Treaty of Free Association between Tokelau and New Zealand). Therefore, Tokelau is an autonomous region (part of the territory) New Zealand. [55] Tokelau is not a subject of international law, foreign relations and defense are carried out by New Zealand. In essence, the Constitution of Tokelau is the charter (statute) of the New Zealand administrative–territorial unit, and Tokeluans are both de facto and legally subjects of New Zealand, born and residing in Tokelau. Thus, the New Zealand legal regime of subsurface use is applicable to Tokelau, taking into account the above restrictions on land turnover. At the same time, there is a special type of land ownership in Tokelau – the property of a nuclear family (common joint property of relatives). Having been born, a person immediately becomes a co-owner of the parents' land plot, as well as all other family members (living relatives). If the family dies completely, then the family property is inherited by the closest family, and not by a separate distant relative. The agricultural sector of Tokelau grows papayas, taro, coconuts and pumpkins for domestic consumption, only fish and seafood are of export importance, the sale of which is the main source of income for the local population and the Tokeluan budget. The territory under consideration has completely switched to energy-saving technologies, electricity production is carried out only by solar panels. Fresh water is in short supply, which determines the level of agriculture.

The Government of Tokelau consists of ministries – government Departments (Government Departments), it is headed by an administrator. The Ministry of Economic Development, Natural Resources and Environment (Sectors Under Economic Development, Natural Resources and Environment) deals with climate change and environmental monitoring, implements an environmental plan for sustainable development, is responsible for agriculture and fisheries, as well as the prevention of environmental pollution. The Ministry of Energy (Department of Energy) is responsible for renewable energy sources, it has implemented a program for the transition to solar electricity, which is currently being supported and developed. Tokelau does not have State bodies for the management of subsoil use, as well as natural resource legislation. Legislation on inland sea waters, territorial sea and contiguous zone, as well as on environmental protection, ecology and biodiversity – typical for New Zealand territories, adopted for Tokelau, which follows from the review of Tokeluan environmental legislation. [56] United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland Pitcairn Islands The Pitcairn Islands [57] is an overseas Territory of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in the Pacific Ocean. The Constitution of the Pitcairn Islands came into force on March 4, 2010 [58], confirming their affiliation to the United Kingdom, represented by the Governor of Pitcairn. [59] The Governor of the Islands issues regulatory legal acts in coordination with the Pitcairn Council (Island Council for Pitcairn), which are regional acts and acts of local self-government at the same time. The State power and the right to make laws of the Pitcairn Islands belongs to the English monarch (article 10 of the Constitution of the Pitcairn Islands), while the island is under the jurisdiction of the Governor-General of New Zealand, who is the High Commissioner of the Pitcairn Islands. The population of this Territory does not exceed fifty people according to the 2021 census; foreign relations, defense and security are carried out by the United Kingdom. Thus, the Pitcairn Islands are directly subject to the jurisdiction and legislation of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Meanwhile, executive and judicial power is exercised by New Zealand institutions, to which the relevant powers are delegated. Despite the constitutional system of courts, the Governor performs the role of a judge (Chief Justice). Since 2010, the islands have had their own Attorney General, customs, border service, liaison officers, as well as environmental authorities and a human rights commissioner. The environmental protection of the British Polynesian Overseas Territory is the most significant business of Pitcairns. The legislation of the Pitcairn Islands [60] does not form a branch of environmental law. [61] By the Decree of the Governor of the Pitcairn Islands of July 7, 2022 (Land Court (Court Registrar) Amendment Ordinance 2022) [62] the Pitcairn Islands Land Court was created as part of one clerk – registrar of land rights, which previously existed only abstractly by virtue of Lands Court Ordinance 2001 [63]. The Marine Environment Protection Regulations of October 11, 2022 (Marine Conservation Regulation 2022) provide for the issuance by a naval officer of fishing permits in the waters of the Pitcairn Islands to persons who have reached the age of 15 at their request. The water area of the Overseas Territory is a conservation area based on the Pitcairn Islands Marine Protected Area Ordinance 2016.[64] Endangered species are protected by Endangered Species Protection Ordinance 2004, and apiaries and beekeeping are an Ordinance to Regulate The Industry of Beekeeping 2001. Taxation in the field of environmental management is limited to land tax on the basis of Land Tenure Reform Ordinance. [65] Payments are charged for the use of the marine environment by tourists and the issuance of fishing permits. Tourists arrive on ships, locals use boats and scooters, which led to the appearance of the Decree on the Prevention of Collisions of Ships (Prevention of Collisions at Sea Ordinance 2001), tourism brings the bulk of the islanders' income. Thus, subsurface use on the Pitcairn Islands is not carried out, environmental protection is entrusted to the prosecutor's office and the public. Regulatory legal acts in force on the Pitcairn Islands are contained on the website of the publication of regulatory legal acts of the United Kingdom. [66] Independent State of Samoa The Independent State of Samoa [67] declared independence from New Zealand on January 1, 1962, previously the state was also referred to as Western or German Samoa, existing next door to Eastern or American Samoa. Meanwhile, the Independent State of Samoa is a member of the British Commonwealth of Nations, and, as a result, receives the Westminster model of governance reflected in the Constitution of The Independent State of Samoa. [68] The head of State is O le Ao o le Malo, elected by the Parliament – Legislative Assembly (consists of 51 members) on the recommendation of the ruling party or party coalition. The Government is formed by three branches of Government under the leadership of the Head of the Independent State of Samoa. Executive power is exercised by the Cabinet of Ministers, headed by the Prime Minister, appointed by the Head of State. O le Ao o le Malo is the second, upper, house of the Samoan Parliament (Parlament). Judicial power is exercised by the Supreme, Appellate and District courts, as well as by a specialized land court.

Land and Titles Court is a court that considers land cases and Matai title cases (Matai titles), denoting tribal possessions withdrawn from circulation. The lands are divided into, firstly, communal (Customary land), which are traditionally owned by local residents collectively (collective property); secondly, private (Freehold land), which are in free civil circulation of individuals; thirdly, state - all those lands that are not classified as communal and private possessions which are located within the state borders, as well as the lands of reservoirs starting beyond the tide line (articles 100 – 104 of the Constitution of the Independent State of Samoa). Communal lands and possessions under the title of Matai may be withdrawn for public or State needs on the basis of a decision of the Parliament of the Independent State of Samoa. Alienation of Freehold Land Act 1972, Customary Land Advisory Commission Act 2013, Land and Titles Act 1981, e Land for Foreign Purposes Act 1993, Land Surveys and Environment Act 1989, Land Titles Investigation Act 1966, Land Titles Registration Act 2008, National Parks and Reserves Act 1974, Planning and Urban Management Act 2004 – Laws governing the turnover of land in the Independent State of Samoa. [69] The Cabinet of Ministers includes 15 ministries, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment – the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of the Independent State of Samoa [70] exercises powers in the field of environmental protection, water and forestry, prevention of natural disasters, elimination of their consequences, sanitary and environmental supervision, management of land resources and geological information and subsoil, He is in charge of cartography and geodesy, monitors climate change, and is responsible for meteorology. Fisheries Management Act 2016, Marine Pollution Prevention Act 2008, Petroleum Act 1984, Maritime Zones Act 1999 regulate the protection of the marine environment from pollution, but not during the exploitation of mineral deposits, but during the transportation of petroleum products imported by the Independent State of Samoa for processing, largely for combustion in thermal power plants, as local hydroelectric power plants freshwater rivers do not provide the country with the necessary electricity. Fishing due to the lack of a fishing fleet, refrigerators and canneries is not developed, harvesting and processing of fruits, palm oil production prevails in agriculture. Biodiversity is provided by the Canine Control Act 2013, Cocoa Disease Ordinance 1925, Quarantine (Biosecurity) Act 2005 and other laws. Thus, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland reserves the lands and mineral resources of the Independent State of Samoa, which is actually in the British protectorate, recreational and agricultural capacities of this country, and also stagnates the fishing industry, which is unable to meet the needs of the local population in marine food, with their excess in the marine environment, in the economic interests of the United Kingdom. Kingdoms. Republic of Kiribati Kiribati (Republic of Kiribati) is a state that declared independence from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on July 12, 1979 [71], uniting two former British colonies: the British Western Pacific Territory (British Western Pacific Territory), as well as the Gilbert and Ellice Islands (Gilbert and Ellice Islands), which has enormous reserves of natural resources. resources in their waters, as well as industrial reserves of phosphates on the islands. [72] The Constitution of Kiribati [73] provides that the positions of head of State and head of Government are occupied by one person – Beretitenti (Beretitenti) – the President [74], who has a deputy (vice-president) appointed from among the ministers and called Kauoman-ni-Beretitenti (Kauoman-ni-Beretitenti). Cabinet – The Government of Kiribati is an executive body consisting of the President, Vice-President and 12 other ministers.[75] The Cabinet is collectively responsible for the implementation of the executive function of the government before the unicameral parliament – Maneaba ni Maungatabu (Maneaba ni Maungatabu), which includes 35 members who adopt the laws of Kiribati (meanwhile, British common law is still applied in this country, which is provided for in the law on the legislation of this republic – Laws of Kiribati Act 1989). Article 8 of the Constitution of Kiribati proclaims equality of all forms of ownership and protection of owners from discrimination. At the same time, the Republican Constitution allocates the property of the British Crown (Crown Property) that arose before the declaration of independence of the state in question and acquired by the Crown after, the property of the Republic of Kiribati, as well as the property of private individuals. Thus, in contrast to the property of municipalities, which is administered on the basis of the law on Local Self–Government – Local Government Act 1984, as well as the law on abandoned lands - Neglected Lands Ordinance 1959 (orphan lands become municipal and are managed by local councils), and the indigenous population (the basis of the emergence of the title - Native Lands Ordinance 1956), community property, crown property is provided for in the Basic law and cannot, unlike State land ownership (State Acquisition of Lands Act 1986), be seized on the basis of a law or judicial act without amending the Constitution of the Republic of Kiribati. The alienation of royal property occurs solely at the will of its holder. The acquisition of new lands by the Crown gives them the status of crown lands.[76] Article 119 of the Constitution of Kiribati provides for a special procedure for the turnover of land in Banaba, where royal land cannot be seized for the purposes of phosphate mining, and private property only with the consent of the local council – a representative body of local self-government, if the owner refused to sell the land for the purposes of mining or transfer it to a subsoil user for rent. The seizure of private land is allowed with proportionate compensation to the owner of the value of the land plot (Land Planning Ordinance 1977, Building Act 2006).[77] Consequently, Article 8 of the Kiribati Constitution essentially guarantees equality of private property (equality of property rights of citizens), but grants the property of the British Crown immunity from the State (Republic of Kiribati) and any other persons, which discriminates against Kiribati and its citizens. Kiribati's economy is based on fishing (granting fishing licenses to legal entities of other countries), the coconut industry, the cultivation of export algae, and the agro-industrial complex. [78] Official statistics conceal the exploitation of seabed minerals in Kiribati, as well as phosphates on land. [79]

It should be noted that the acts on licensing of subsoil use were adopted in the colonial period, there are two of them: Foreshore and Land Reclamation Ordinance 1969, Mineral Development Licensing Ordinance 1978. Environmental protection is based on risk management (Natural Disaster Act 1993), it is carried out on the basis of the Environment Act 1999, Marine Zones (Declaration) Act 1983, Importation of Animals Ordinance 1919, Recreational Reserves Act 1996, Wildlife Conservation Ordinance 1975. [80] The Phoenix Islands at the same time have specialized environmental legislation: Phoenix Islands Protected Area Regulations 2007, Phoenix Islands Protected Area Conservation Trust Act 2009. The natural resources of this special Territory are managed by the Ministry of Coast and Phoenix Islands Development (Ministry of Line and Phoenix Islands Development). [81] A significant part of Kiribati is a reserve of natural resources of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Agriculture Development [82] and Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development (Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development). [83] The state company Te Atinimarawa is engaged in the extraction of gravel and sand in the island water area, no other licenses for subsurface use in the marine environment have been issued by the state. The Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development independently conducts geological exploration of the vast exclusive economic zone of the Republic of Kiribati by the Geological and Geophysical Research Department. At present, significant reserves of manganese nodules, cobalt crust, metal-bearing deposits, and phosphates have been discovered. Thus, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland forms a reserve of minerals, the development of which is not carried out. [84] The Ministry of Environment, Lands and Agricultural Development is responsible for land management, cartography, monitoring and environmental protection, supervision of land use and subsoil use. It accepts applications for the exploitation of the subsoil of the islands, first of all, for the exploration and extraction of phosphates and common minerals. Meanwhile, with the exception of licenses issued during the colonial period, no licenses were issued to private individuals for subsurface use. The Republic of Kiribati itself is engaged in the geological study of its islands. Kingdom of Tonga Tonga (Kingdom of Tonga) is a Polynesian state that gained independence from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on June 4, 1970. At the same time, the Constitution of 1875 with the latest amendments of 2016 is in force in the kingdom. [85] The Tongan Monarchy forms a Cabinet government headed by the Prime Minister. The Monarch heads the Privy Council (Privy Council), consisting of members of the government. Ministers are appointed by the Sovereign from among twenty-five parliamentarians. The Legislative Body (The Legislative Assembly of Tonga) includes 9 nobles (hereditary mandates) and 17 elected deputies. The Legislative Assembly issues draft laws adopted or rejected by the King of Tonga. The Head of State appoints governors – heads of regions, as well as judges at all levels. [86] There are district, Appellate and Supreme Courts of the Kingdom of Tonga in the State. [87] In 1991, a Land Court was established, acting on the basis of Land Court Rules 1991 [88] as amended in 2020. The lands in the Kingdom of Tonga belong to one owner – the King of Tonga, as specified in article 104 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Tonga. The lands are inalienable and are in the eternal monarch's property, allotments are granted to the nobles by the grace of the king in a lifetime inherited possession, which can be terminated by the monarch. The owner's lands are inherited together with the titles of nobility, the extortionate immovable property of the nobles is removed from the lifetime inherited possession, it returns to the king, the movable extortionate property becomes the property of the Tongan monarch. Landowners may lease real estate for a period not exceeding 99 years with the consent of the Cabinet, and for a period exceeding 99 years with the consent of the Privy Council (article 114 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Tonga). There are 19 ministries in the state,[89] The Ministry of Lands, Geodesy and Natural Resources (The Ministry of Lands, Survey and Natural Resources) manages lands, mineral resources and energy. It consists of five departments: land, geodesy, natural resources, geographical information systems, spatial planning; their activities have a regulatory legal framework. The Land Act of 1927 (Land Act 1927)[90] as amended in 2020, in the first article confirms the royal ownership of all the lands of the state, provides for the creation of a land Court, defines the special powers of the Ministry of Lands, Geodesy and Natural Resources in the field of land use and land management. On the basis of article 3 of the Minerals Act of 1949 (Mineral Act 1949), as amended in 2020, all minerals in the jurisdiction and boundaries of the exercise of sovereign rights by the State belong to the monarch and are in the royal reserve. Mineral exploration licenses are granted by the Ministry of Lands, Geodesy and Natural Resources, mining licenses are granted by the Cabinet of the Kingdom of Tonga. The validity period of the license is determined when they are issued by an authorized body, which is a feature of Tongan legislation [91], since in other states the maximum validity period of the license is provided by law. The Ministry of Lands, Geodesy and Natural Resources may extend licenses at the end of their validity period (articles 5-12 of the Minerals Act of 1949). The issuance of subsurface use licenses is limited by article 13 of the law under consideration to the range of subjects of the right to use subsurface resources: only Tongan legal entities and “British subject” – companies registered in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, as well as private organizations of the Republic of Ireland equated to them, can apply for the right to use subsurface resources earlier (until December 6 1922) was part of the United Kingdom. Consequently, the minerals of the Kingdom of Tonga are the reserve of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, as well as the Tongan King, who is under the patronage of the British Government. In form, Tonga has always been a monarchy under the leadership of its sovereign, legally the English monarch has never been the head of state in this country, but in fact this is not the case. The King of Tonga recognizes de facto vassalage to the English crown.

The waters of the Kingdom of Tonga have clear borders agreed with other States. The sovereign rights of the Kingdom, the legal regimes of sea waters, and the exploitation of mineral deposits in the ocean are regulated by the Maritime Zones Act 2013 [92] as amended in 2020. In 2014, the Law on Seabed Minerals (Seabed Minerals Act 2014) was adopted [93], effective as amended in 2020. The law replaces the concept of "sovereign rights" with the concept of "national jurisdiction", which applies to the entire shelf and exclusive economic zone of the Kingdom of Tonga, which, on the basis of the fourth article of the law, entirely belong to the Tongan monarch. The Tonga Seabed Minerals Authority manages the subsoil use in the waters of this state – it is an interdepartmental government structure – the council of functionally related ministries. At the same time, the decision on granting the right to use offshore subsurface areas – blocks (article 29 of the Law on Seabed Minerals) is made by the Cabinet. Part five of the law under consideration regulates the submission of applications for the exploration (search) of seabed minerals, and the sixth part – their extraction. These parts provide a system of payments for the use of mineral resources. When mining continues, licenses are automatically renewed every 5 years, this Tongan feature is provided for in Article 72 of the law - Seabed Minerals Act 2014. Its adoption was the result of the discovery of significant industrial reserves of manganese, gold, cobalt and other metals on the ocean floor as a result of the geological study of the seabed. Meanwhile, taking into account the limited number of persons potentially allowed to use the subsoil, the Kingdom of Tonga issues grants for the geological study of the seabed to determine the size of mineral reserves in the ocean in order to provide raw materials for the British and Tongan economy in the future. The development of mineral resources, which began in the last decade, required the adoption in Tonga of the Water Resources Act 2020, which protects the marine environment from man-made impacts, providing for monitoring of the waters of Tonga. Kingdom of Tuvalu Tuvalu (Tuvalu) [94] is a Polynesian monarchy that declared independence from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland on October 1, 1978, formerly known as the British protectorate – Ellis Islands, separated from the British colony – Gilbert and Ellis Islands, transformed into the Republic of Kiribati. Meanwhile, on the basis of part 1 of Article 48 of the Constitution of Tuvalu [95], the head of this State is the English monarch, represented by the Governor-General. The Head of State forms the Cabinet, appoints the Prime Minister and other Cabinet ministers exercising executive power. The sovereign accepts or rejects parliamentary bills, the bill adopted by the monarch becomes a normative legal act of parliament. Thus, the Kingdom of Tuvalu implements the Westminster model of governance. The High Court of Tuvalu is the highest judicial instance, however, the head of Justice (Chief Justice) is the head of State – the sovereign. The Court of Appeal for Tuvalu considers complaints against decisions of the district courts. The Constitution of Tuvalu provides for the creation of other courts at the will of the Parliament, consisting of 12 members (paragraph 6 of the section "Transitional provisions"). Ministers are appointed by the Sovereign from among parliamentarians, they propose to the Sovereign the candidacies of appeal and district judges. Consequently, the highest power in Tuvalu is concentrated in the hands of no more than three dozen people who form the rest of the state apparatus in the interests of the sovereign of Tuvalu – the King of England. This means that the democratic state of Tuvalu is under the control of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, which predetermines the legislative model of subsoil use management of this Polynesian country. [96] It is obvious that a group of British dependent territories has regulatory legal acts in the field of ecology and nature management, similar in content and adopted (modified) approximately in parallel. [97] Native Lands Ordinance 1956 – the same law as in the Republic of Kiribati establishes the title and regime of indigenous lands. The Foreshore and Land Reclamation Act 1969 regulates the regime of coastal lands, as well as land reclamation. The Crown Acquisition of Lands Act 1954 provides for the acquisition of lands by the British Crown for public needs, the reservation of natural objects and environmental protection, which are withdrawn from circulation. This law in Tuvalu remained unchanged, in Kiribati it was changed in 1986. Neglected Lands Act 1959 – the colonial heritage of the United Kingdom shared with Kiribati. Noteworthy is the Closed Districts Act of 1936 (Closed Districts Act 1936) [98], the fifth article of which indicates the possibility of access to the closed territories of Tuvalu only by the decision of the authorized minister of persons with a license, but does not specify which one. It follows from the context of this regulatory legal act that radioactive minerals used for the production of nuclear energy and nuclear weapons by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland are being exploited in restricted access areas. The Conservation Areas Act 1999 provides for the formation of protected areas in Tuvalu in order to preserve natural heritage sites, first of all, such territories are created in the Pacific Ocean. This indicates that the seabed and subsurface of the underwater areas of these territories are rich in minerals, the extraction of which has been postponed until demand. Marine Resources Act 2006 regulates the extraction of marine resources in the Kingdom. While the licensing of subsurface use is regulated by the special Law on Licensing of Mineral Development of 1977 (Mineral Development Licensing Act 1977) [99]. The authorized Minister, on the basis of the application of the subsoil user, issues a license for the right to use the subsoil, containing the boundaries of the license area, the term and conditions of use of the subsoil. Licenses for the right to use mineral resources are combined (exploration and production) and are issued for no more than 25 years with the possibility of continuing subsoil use after the expiration of the license for no longer than a quarter of a century – by decision of the authorized Minister (part six of the Law on Licensing of Mineral Development of 1977). Petroleum Act 1965 [100] regulates the turnover of oil and petroleum products in Tuvalu, the construction of hydro-carbon cluster facilities (as amended in 2008). Marine Pollution Act 1992 [101] (as amended in 2008) protects the marine environment from pollution during the exploitation of natural resources.

The Ministry of Natural Resources of the Government of Tuvalu [102] administers the listed laws on environmental protection and natural resources, issues licenses for fishing and subsurface use, monitors climate change, manages land, water and forestry, and also carries out international cooperation in the environmental sphere. The Ministry of Transport, Energy and Tourism [103], as well as the Ministry of Fisheries and Trade [104] assist the Ministry of Natural Resources in carrying out its functions. Thus, the Kingdom of Tuvalu has the legislative framework and State apparatus necessary for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to activate the reserved reserves of Tuvalu natural resources. French Republic France is a unitary state, consisting of 26 subjects – administrative territorial units of the first level. [105] 18 French regions include 101 departments, of which 13 regions are located in Europe: 96 departments and the Lyon Metropolitan Area; 5 of the 18 French regions are overseas regions (Guadeloupe; Martinique; Guiana; Reunion; Mayotte), each of which has the status of a department. In addition, the French Republic includes 8 more entities: 5 overseas communities (French Polynesia; Wallis and Futuna Islands; Saint Pierre and Miquelon; Saint Barthelemy; Saint Martin) and 3 three overseas special administrative-territorial entities: New Caledonia; Clipperton; French Southern and Antarctic Territories. Guadeloupe, Guiana, Martinique, Reunion, Mayotte, Saint-Barth?lemy, Saint-Martin, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon, the islands of Wallis and Futuna and French Polynesia have the status established in article 73 of the French Constitution. Overseas administrative-territorial entities have charters that take into account the own interests of each of them as part of the Republic (article 74 of the Constitution of France). Charters may provide for the autonomy of the relevant subjects of the state and limit the application of French organic laws on them, change the subject matter of regional legislative authorities, detracting from the Republican parliament. French Polynesia French Polynesia (Polyn?sie fran?aise) [106] is an overseas community of the French Republic, formed on the basis of article 73 of the Constitution of France. It applies French laws, partly adapted to local conditions on the basis of the Republican constitution. The area of French Polynesia is approximately twice the area of Europe, which determines the economic importance of the region. Most of this overseas community of the French Republic consists of the water area – the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone. Jean Guezennec, Christian Moretti, Jean-Christophe Simon in the book "Les substances naturelles en Polyn?sie fran?aise : ?tat des lieux" [107] claim that there is no exploration and development of minerals in the waters of French Polynesia. Allegedly, the fishing industry, the cultivation of pearls, edible algae, the coconut industry and tourism are the basis of the economy of this French province remote from the Old World. Doctor of Public Law Herv? Raimana Lallemant-Moe (Herv? Raimana Lallemant-Moe) in the book "Introduction A L'etude Du Droit Del'environnement De La Polynesie Francaise" [108] indicates that the legislation of the region is adapted for the extraction of minerals of the exclusive economic zone, including environmental protection acts. French Polynesia has its own environmental code of 2017 (Code de L'environnement de la Polynesie Fran?aise). [109] If specialized legislation on the protection of nature is adopted, then an impact on the environment is being carried out. Lucile Stahl from the Lyon Institute of Environmental Law confirms this hypothesis in the article "Le Code de l'environnement de la Polyn?sie fran?aise" [110]: as a result of geological study, data on significant reserves of minerals of the seabed and recoverable reserves of marine subsoil were obtained, after which a regulatory framework for their development was prepared. However, while these natural resources are not exploited, they make up a reserve fund. The natural resources of Polynesia can be claimed by France in case of economic necessity of their industrial use.

The High Commissioner of the French Republic in French Polynesia [111], appointed by the President of France, manages the environment, taking into account the special economic importance of the waters of the region. The Ministry of Ecology, Sustainable Development and Energy of French Polynesia (Minist?re de l'?cologie, du D?veloppement durable et de l'?nergie) includes the Marine Affairs Service (Le service des Affaires maritimes de la Polyn?sie fran?aise), which prevents marine pollution and deals with the elimination of the consequences of negative anthropogenic impact in the ocean. The Office of State Actions at Sea (Bureau de l'Action de l'etat en Mer) coordinates the civil and military administrations of the region in terms of the suppression of illegal activities in the waters of French Polynesia and environmental protection. In addition, a mission to monitor the consequences of nuclear tests of the Pacific Experimental Center (municipalities – Gambier, Hao, Reao and Tureia) is being implemented in the Tuamotu and Gambier archipelagos with the participation of the Regional Ministry of Solidarity and Health (Minist?re des Solidarit?s et de la Sant?). At the same time, L'Agence de l'Environnement et de la Ma?trise de l'Energie, the state operator of the transition to new environmental and energy standards, implements environmental protection projects as an environmental and energy management agency subordinate to the High Commission (haut-commissariat) and the Ministry of Ecology, Sustainable Development and Energy of French Polynesia. The French Bureau of Biodiversity (Office Fran?ais de la Biodiversit?) unites the missions of the National Directorate of Hunting and Wildlife (Office National de la Chasse et de la Faune Sauvage) and the French Agency for Biodiversity (Agence fran?aise pour la biodiversit?): to support policy in the field of aquatic bioresources and biodiversity; to manage natural resources; to coordinate environmental police and environmental supervision; to study the environment; to manage the marine environment and the coast. Consequently, the French Republic, through the High Commissioner, the High Commissariat and the territorial bodies of the French executive authorities, as well as regional executive authorities, exercises leadership in the field of the environment and natural resources. Thus, the overseas community of the French Republic has its own environmental legislation, adapted to local conditions, implemented by both the French administration and the regional one, with the help of coordination centers linking these management links into a single system. The natural resource law of the French Republic operates in French Polynesia, it is implemented by administrations of both levels. Wallis and Futuna Wallis and Futuna (Wallis-et-Futuna) [112] is an overseas community of the French Republic, formed on the basis of article 73 of the Constitution of France. It applies French laws, partly adapted to local conditions on the basis of the Republican Constitution, including the natural resource law of the French Republic. There is no economic activity in the field of subsurface use in this region, as indicated in the current economic report (Donn?es Economiques) of the prefectures of Wallis and Futuna Islands. [113] The Overseas Community is headed by the Prefect of the islands of Wallis and Futuna (Pr?fet des ?les Wallis et Futuna), appointed by the President of France in consultation with the Minister of Internal and Foreign Affairs of the Republic, and responsible for the implementation of the organic laws of the State in the region under consideration. The Ministry of Environmental Integration and Territorial Unity of the French Republic (Minist?re de la Transition ?cologique et de la Coh?sion des territoires) together with the Ministry of Energy Integration of the French Republic (Minist?re de la Transition ?nerg?tique) are responsible for environmental protection and nature management of the Wallis and Futuna Islands. Currently, the contractor – a legal entity – Fenua is completing the transfer of the overseas community to solar energy through the installation of batteries that generate electricity from sunlight. [114] By Decree of the Prefecture of the Wallis and Futuna Islands No. 97-060 of February 12, 1997, an environmental service (Service de l'Environnement) was established in the French subject, responsible for environmental protection, biodiversity and conservation of species diversity, control of nature pollution and waste management, development of renewable energy sources, environmental education. [115] In the field of ecology and nature management, Wallis and Futuna accept regional environmental and energy planning documents, and there are implemented environmental development programs in the region. [116] The overseas Community of the French Republic of Wallis and Futuna does not have regional legislation on subsoil and subsoil use, as well as specialized management bodies in this area. Thus, the considered French region is a recreational and raw material reserve that will be in demand if necessary. Republic of Chile Isla de Pascua (Isla de Pascua) is a district (province) and the commune of the same name (unit of local government) of the region (region) Valparaiso (Valpara?so) of the Republic of Chile, the same as the commune of Juan Fern?ndez, is a Polynesian territory in the Pacific Ocean. Isla de Pasqua and Juan Fernandez Provinces

The designated areas have a special status and history of the development of land legislation, taking into account their historical significance. [117] At the same time, one cannot agree with the Argentine lawyer Maria PereyraUhrl, who allocates private, public, including military, and traditional lands of these areas under Chilean law. [118] The Civil Code of the Republic of Chile 1855 [119] (Chili Civil Code 1855) as amended in 2000 [120] understands by "indigenous" (local resident) the indigenous Chileans who have lived on the territory of the republic historically, that is, the Indians of South America. Polynesian tribes are aborigines of Maui ("nativo" in Spanish, and in English – "aborigen") and have no genetic relationship with the Chilean Indians. In addition, Isla de Pasqua and Juan Fernandez became part of the Republic of Chile almost three decades after the entry into force of the C?digo Civil 1855, which does not imply the extension of the title of "traditional lands" to the local residents of the territories annexed by military means, which have been state-owned since the inclusion of the conquered islands into the republic as municipal the district. The sovereignty and ownership of the land of the South American States, whose territory before the conquest of the Chilean Republic were the corresponding islands, have ceased, as well as the unformed and non-based property of the aborigines. In essence (in fact), the previous Latin American colonizers, unlike the British, did not recognize any rights to the land of the controlled territories for local residents. Consequently, all the lands of the Chilean provinces in question became republican at the time of annexation of the corresponding territory, and then were transferred to private individuals on civil legal grounds into private ownership, on the basis of public acts – into municipal ownership and permanent indefinite use of indigenous communities. Thus, the lands of the aborigines of these areas, unlike continental Chile, are state–owned and are owned and used by the descendants of the indigenous population at the will of the owner of these lands - the Chilean Republic. This is a feature of the ownership of the land of the Chilean territories in Polynesia. Subsurface use on the territory of Isla de Pasqua and Juan Fernandez is not conducted, as they are UNESCO World Cultural Heritage sites and are studied by archaeologists, especially Easter Island, where there are monolithic stone statues – moai, testifying to subsurface use in ancient times – the extraction and processing of stone. The Republic of Chile is a unitary State and extends its sovereignty and environmental legislation, legislation on subsoil and subsoil use, environmental protection, and republican water areas to provinces (municipalities – districts of the Valparaiso region) Isla de Pasqua and Juan Fernandez without any exceptions and exceptions. Valparaiso, in turn, in regional regulatory legal acts does not provide for the specifics of nature management in its areas.

References

1. Tcherkezoff, Serge (2011). Inventing Polynesia: Transformations of Cultural Traditions in Oceania. Changing Contexts, Shifting Meanings. (pp. 123-138). doi:10.21313/hawaii/9780824833664.003.0008.

2. Hanlon, David (2009). The “Sea of Little Lands”: Examining Micronesia’s Place in “Our Sea of Islands”. The Contemporary Pacific by University of Hawai‘i Press. Vol. 21, Number 1, pp. 91–110.

3. Rainbird, Paul (2004). The Archaeology of Micronezia. Cambridge University Press.

4. Ryan, Tom (2002). 'Le Pre´sident des Terres Australes': Charles de Brosses and the French Enlightenment Beginnings of Oceanic Anthropology. Journal of Pacific History 37(2), pp. 157-86. doi:10.1080/0022334022000006583.

5. Rabba, N.P. (1972). Polynesia. An essay on the history of the French colonies (late XVIII-XIX centuries). Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Institute of Oriental Studies. Moscow: Nauka Publishing House.

6. Pale, S.N. Ethnopolitical conflicts in Oceania in the postcolonial period (on the example of French possessions in the Pacific Ocean, Fiji and the Solomon Islands). Dissertation for the degree of Candidate of Historical Sciences. Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Moscow.

7. Okunev, I.Y. (2011). Modeling of spatial factors of development of microstates and territories of Oceania. Dissertation for the degree of Candidate of Political Sciences. MGIMO (U) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia. Moscow.

8. Manin, Ya.V. (2021). The legal regime of subsoil use in the United States of America. Administrative and municipal law, 1. pp. 80-97.

9. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/

10. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/dobor/

11. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/boc/

12. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/occl/

13. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/dar/

14. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/docare/

15. Retrieved from https://dlnreng.hawaii.gov/

16. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/dofaw/

17. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/shpd/

18. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/ld/

19. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/dsp/

20. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/rules/

21. Retrieved from https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/hrsall/

22. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/boards-commissions/blnr-board/#:~:text=The%20Board%20of%20Land%20and,of%20Land%20and%20Natural%20Resources

23. Retrieved from https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/cwrm/aboutus/commission/

24. Retrieved from https://files.hawaii.gov/dlnr/cwrm/regulations/Code174C.pdf

25. Retrieved from https://www.capitol.hawaii.gov/hrscurrent/vol03_ch0121-0200d/hrs0128d/hrs_0128d-.htm

26. Retrieved from https://ceq.doe.gov/docs/laws-regulations/state_information/HI_NEPA_Comparison_22Dec2015.pdf

27. Retrieved from https://www.americansamoa.gov/

28. Retrieved from https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands

29. Retrieved from http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/98671/117487/F-1956155712/USA98671.pdf

30. Retrieved from https://www.americansamoa.gov/jobs

31. Retrieved from https://coast.noaa.gov/digitalcoast/contributing-partners/american-samoa-dmwr.html (date of access: 09.05.2023).

32. Salikov, M.S. (1998). Comparative legal study of the federal systems of Russia and the USA. Dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Law. Ural State Law Academy. – Yekaterinburg

33. Irkhin, I.V. (2018). Constitutional and legal status of unincorporated territories of the USA. Jurisprudence. Vol. 62, No. 3. pp. 484–500.

34. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_r.pdf

35. Manin, Ya.V. (2022). The legal regime of subsoil use in the United States of America. Administrative law and practice of administration, 4, pp. 1-27.

36. Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/60530e114.pdf

37. Retrieved from https://www.pmoffice.gov.ck/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Te-Kaveinga-Iti-5-Mataiti-Digital.pdf

38. Retrieved from https://www.pmoffice.gov.ck/our-work/renewable-energy-development/

39. Retrieved from https://www.pmoffice.gov.ck/national-research-council/

40. Retrieved from https://www.pmoffice.gov.ck/our-work/cabinet-services/

41. Retrieved from https://www.countryreports.org/country/CookIslands/natural-resources.htm

42. Retrieved from https://www.mmr.gov.ck/what-we-do/

43. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5cca30fab2cf793ec6d94096/t/5d3f683993ea3f0001b7379c/1564436729995/Seabed+Minerals+Act+2019

44. Retrieved from https://www.sbma.gov.ck/010834858921

45. Retrieved from https://www.sbma.gov.ck/phases-of-sbm-activity

46. Retrieved from https://www.sbma.gov.ck/licences

47. Retrieved from https://www.sbma.gov.ck/partners

48. Retrieved from https://www.gov.nu/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/niue_constitution_ul2022.pdf

49. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1974/0042/latest/whole.html#DLM413400

50. Retrieved from https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/niu88454.pdf

51. Retrieved from https://niue-data.sprep.org/group/236

52. Retrieved from https://www.sprep.org/attachments/Legal/REVIEWS_ENV._LAW/Niue.pdf

53. Retrieved from https://www.sprep.org/attachments/Publications/EMG/sprep-legislative-review-niue.pdf

54. Retrieved from https://www.tokelau.org.nz/About+Us/Government/Self+Determination+Package/Constitution+of+Tokelau.html

55. Retrieved from https://www.tokelau.org.nz/About+Us/Government/Self+Determination+Package/Summary+of+the+Treaty+of+Free+Association.html

56. Retrieved from https://www.sprep.org/attachments/Publications/EMG/sprep-legislative-review-tokelau.pdf

57. Retrieved from https://www.government.pn/home

58. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2010/244/introduction/made

59. Retrieved from https://library.puc.edu/pitcairn/pitcairn/govt.shtml

60. Retrieved from http://www.pitcairn.pn/Laws/Revised%20Laws%20of%20Pitcairn,%20Henderson,%20Ducie%20and%20Oeno%20Islands,%202017%20Rev.%20Ed.%20-%20Volume%201.pdf

61. Retrieved from https://www.government.pn/environment

62. Retrieved from https://www.pitcairnlaws.epizy.com/?i=1

63. Retrieved from https://www.pitcairnlaws.epizy.com/Lands%20Court%20Ordinance.pdf

64. Retrieved from https://www.pitcairnlaws.epizy.com/Cap%2048%20-%20Pitcairn%20Islands%20Marine%20Protected%20Area%202017%20Rev%20Ed.pdf

65. Retrieved from https://www.pitcairnlaws.epizy.com/Land%20Tenure%20Reform%20Ordinance.pdf

66. Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/

67. Retrieved from https://www.samoagovt.ws/

68. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/44021/124322/F-82949215/WSM44021.pdf

69. Retrieved from https://samoa-data.sprep.org/system/files/sprep-legislative-review-samoa.pdf

70. Retrieved from https://www.mnre.gov.ws/

71. Retrieved from http://www.paclii.org/ki/legis/consol_act/cok257.pdf

72. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents/44281-013-kir-iee-01.pdf

73. file:///C:/Users/drman/Downloads/KIR5305.pdf

74. Retrieved from https://www.president.gov.ki/

75. Retrieved from https://www.president.gov.ki/government-of-kiribati/cabinet.html

76. Retrieved from https://constitutions.unwomen.org/en/countries/oceania/kiribati?provisioncategory=682edf00e8e04dd9a47a71db07e2583f

77. Retrieved from https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Kiribati_2013.pdf?lang=en

78. Retrieved from https://www.countryreports.org/country/Kiribati/imports-exports.htm

79. Retrieved from https://www.countryreports.org/country/Kiribati/natural-resources.htm

80. Retrieved from https://www.sprep.org/attachments/Publications/EMG/sprep-legislative-review-kiribati.pdf

81. Retrieved from https://www.mlpid.gov.ki/

82. Retrieved from https://www.melad.gov.ki/

83. Retrieved from https://fisheries.gov.ki/

84. Retrieved from https://fisheries.gov.ki/geoscience-division/

85. Retrieved from https://www.commonwealthgovernance.org/countries/pacific/tonga/constitution/